Louis Daguerre: The Frenchman Who Gave Birth to Photography

Mahacaraka® Press

It's the early nineteenth century, and no one has seen a photograph yet. Paintings are still the preferred medium for capturing moments in time. Artists spend hours, if not days, working on canvases to capture a fleeting expression or a stunning landscape. Imagine the joy and astonishment that people felt when they first saw an image generated entirely by light—no brushes, no pigments, just light and chemistry. This is the world Louis Daguerre entered. His creation, the daguerreotype, irrevocably altered not only art, but also the way we see, remember, and record life.

Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre was not always obsessed with photography. Daguerre, born in 1787, grew up in the little French town of Cormeilles-en-Parisis. As a young man, he was drawn to fine arts and began his career as a painter, subsequently becoming a set designer for theatre shows in Paris. It was during these early endeavours that his passion for realistic, atmospheric effects emerged. Daguerre was well-known for his magnificently painted theatrical backdrops and involvement in scenic illusions through the Diorama, a prominent Paris attraction. The Diorama was well-known for its huge displays that employed creative lighting techniques to create the appearance of movement. Daguerre aimed to recreate reality rather than simply capture a scene. He was well positioned for what came next—he'd try to capture that beauty in a new way: photography.

Daguerre did not invent photography, but he played an important part in its early development. Enter Nicéphore Niépce, a French inventor who had been conducting his own photography experiments. Niépce invented a technique that used bitumen-coated plates to capture extremely primitive images. The process was painfully slow, and the photographs were hazy at best. However, when Niépce collaborated with Daguerre in 1829, things began to move considerably more quickly.

Niépce and Daguerre's cooperation lasted until Niépce died in 1833. Undeterred, Daguerre continued on his own, improving the methods they had developed. His big breakthrough came when he discovered that exposing iodine-sensitized silver plates to light for a set amount of time resulted in crystal-clear images that did not fade instantly (a major drawback with earlier forms of photography).

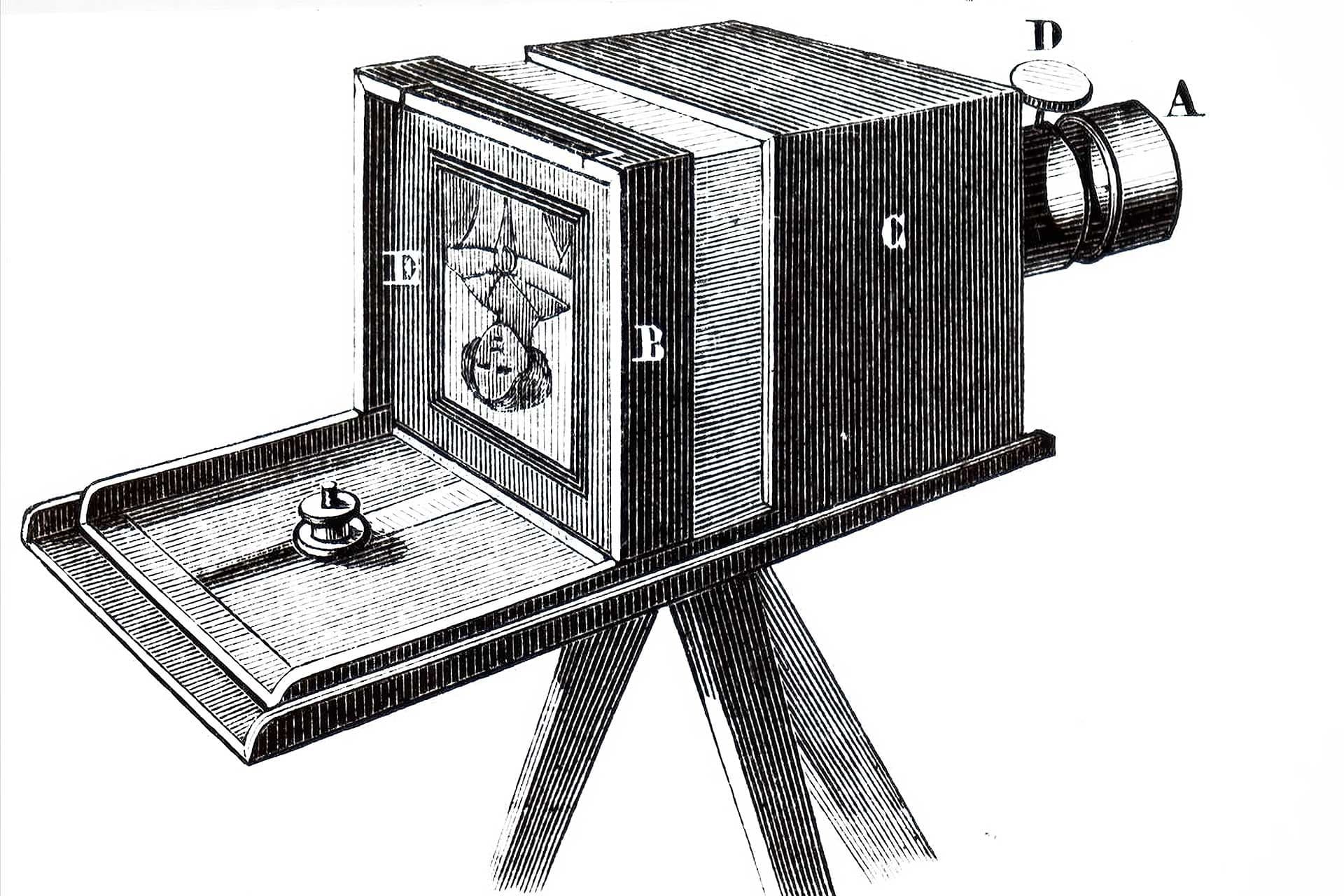

In 1839, Daguerre introduced the world to the daguerreotype. He had worked out how to permanently hang onto a moment in time by combining silver-plated copper and sulphur fumes to "develop" the image and using a unique sealing procedure to set it in place. This was monumental.

Daguerre's creation was unlike anything anybody had seen before. When the French government learnt about it, they realised they were dealing with something revolutionary. In August 1839, in a remarkably modern act, the French government bought the rights to Daguerre's method and declared it a gift "free to the world." That's correct—they essentially invented "open-source" photography over 180 years ago!

With the method in the public domain, experimental artists, scientists, and curious minds all over the world began generating their own daguerreotypes. Photography was no longer limited to a small group of tinkerers; it was now available to anybody with access to the reasonably inexpensive supplies.

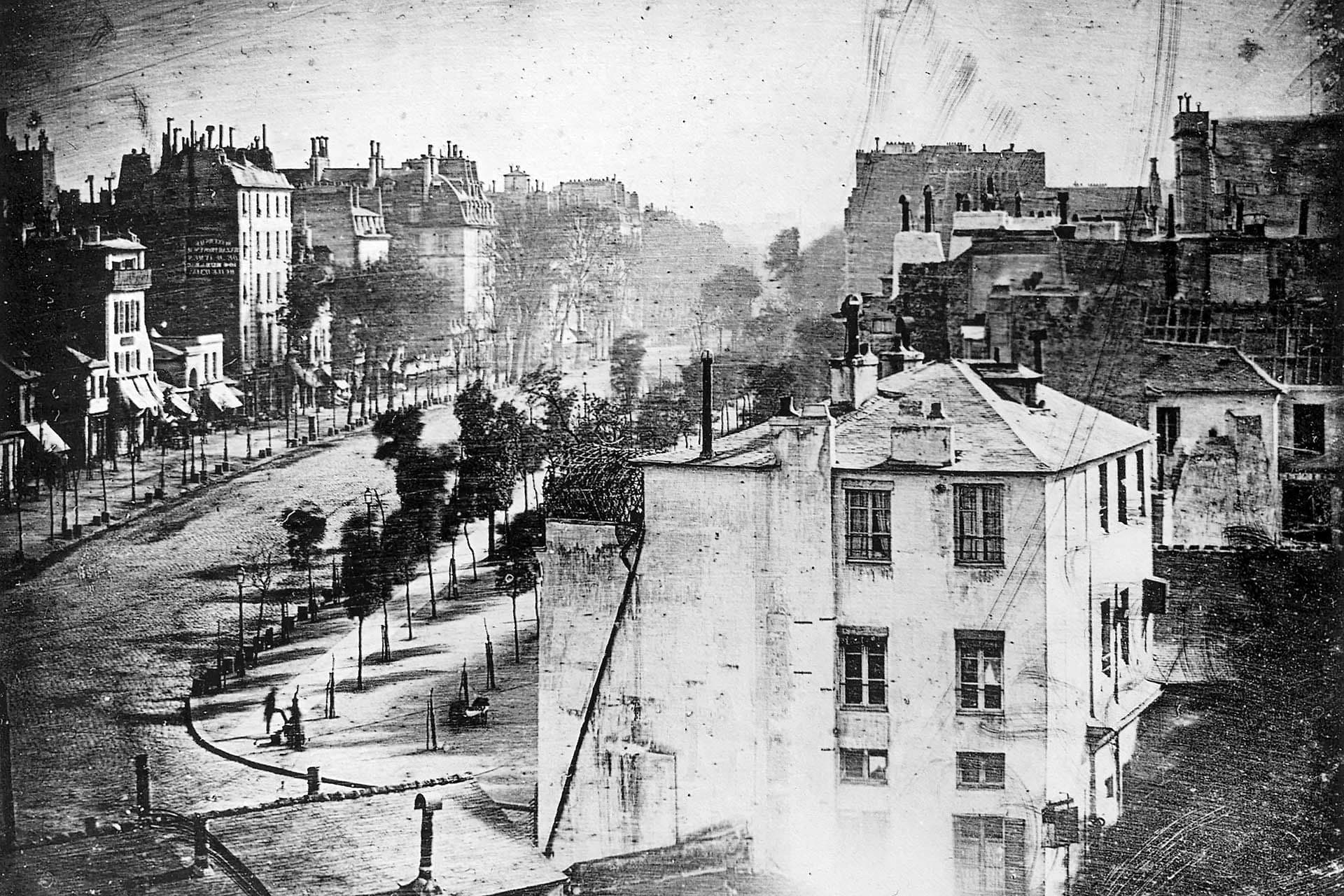

One of the most appealing aspects of the daguerreotype was its unparalleled ability to capture lifelike detail. These photographs were extremely sharp, allowing viewers to see textures and characteristics like never before in any medium. Portraits, landscapes, and cityscapes that used to take painters months to complete could now be caught in minutes. It was a technological marvel that instantly put photography on the map. Literally.

By the mid-1840s, daguerreotype studios were popping up in major cities across Europe and the United States, and photographers had become the new artists in town. It's vital to emphasise that the process wasn't without drawbacks. Early daguerreotype exposure times could range from 10 to fifteen minutes. To avoid blurred findings, subjects had to sit totally still. This meant that, over time, stoic expressions became a trademark of early photography—not the spontaneous, candid moments we can capture now with a mere tap on our smartphones!

Furthermore, generating a daguerreotype required meticulous effort. The plates were sensitive to chemicals and light before being exposed, so handling them properly was critical to ensuring the image was sharp and intact. The entire process was labour-intensive and required a high level of expertise.

Despite these limitations, daguerreotypes remained quite popular, particularly for portraiture. People who had never been painted before—most people couldn't afford to commission a portrait, after all—were suddenly able to pose for a daguerreotype and have a concrete image of themselves or their loved ones. For the first time in history, the middle class gained access to something formerly held only for royalty or the ultra-privileged: a visual record.

Interestingly, Daguerre was not a particularly good photographer. While he continued to improve the daguerreotype technique, most of his popularity was based on inventing and promoting the technology rather than actually employing it.

Surprisingly, by 1850, Daguerre's daguerreotype was already facing competition. Various new photography processes emerged, posing a challenge to the daguerreotype's often-complicated procedure. One of the biggest disadvantages of this technology was that it produced only one, unique image. Once the exposure was made on a plate, it was over. If you wanted a different image, you would have to retake the photo. Other techniques, such as the calotype invented by William Henry Fox Talbot, established the concept of a negative that could make many prints, which was extremely significant for the future of photography.

Nonetheless, Daguerre's significance cannot be underestimated. His method was the first to become widely accepted and commercially successful. It spanned the gap between invention and art, allowing people to embrace this new magical technology in ways that no one had imagined conceivable only a few years before.

Though the daguerreotype had gone out of favour by the 1860s, Louis Daguerre's impact lives on in every photograph we take today. His work established the groundwork for future inventors to build upon, which is exactly what any pioneer wishes for. Photography is an important part of modern communication, art, and documentation, but it all began with a flash of light and a silver plate. From early static portraits of stern-faced sitters to the casual pictures we share on social media today, there is a direct line back to Daguerre.

So, the next time you take a smartphone photo, remember the Frenchman who was fascinated by light and reality. Consider Louis Daguerre, the man who observed the world not only with an artist's eye, but also with a visionary's drive. Photography, which most of us take for granted today, began as a man's bold goal of pushing boundaries and permanently changing the way we capture time.