In an age when enormous parts of the planet remained hidden in mystery, one man’s unwavering pursuit of knowledge would redraw the world’s maps and permanently change the trajectory of exploration. Captain James Cook, a name synonymous with seafaring and discovery, set out on trips that would connect continents and cultures, making an unforgettable effect on history.

James Cook was born on 27th October 1728, in the little village of Marton-in-Cleveland, England, as the second of eight children in a humble farming family. His father, also named James, worked as a farm labourer, while his mother, Grace Pace, encouraged the family’s ambitions. Cook and his family relocated to the nearby community of Great Ayton when he was eight years old, where his father’s business recognised the young boy’s ability and paid for his education.

Despite his minimal formal schooling, Cook shown a quick intelligence and an early interest in the sea. At the age of 17, he moved to the coastal town of Whitby to apprentice under John Walker, a Quaker shipowner. He learnt the nuances of seamanship on coal colliers, which were robust vessels that hauled coal along England’s coastline. These formative years sharpened Cook’s navigational abilities and resilience, setting the framework for his future endeavours.

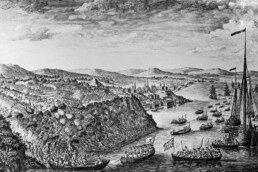

Cook made a key decision in 1755, as tensions between Britain and France escalated. He volunteered for the Royal Navy, passing up a potential career in the commerce fleet. His timing was fortunate; the Seven Years’ War was on the horizon, offering numerous prospects for development. Cook’s proficiency rapidly drew the notice of his superiors. He mastered surveying and cartography, which he used during the siege of Quebec to methodically chart the dangerous St. Lawrence River. His charts proved useful during the British attack on the French fortress.

By the war’s end, Cook had established himself as a capable and dependable officer. His outstanding work mapping Newfoundland’s shoreline over the next few years cemented his reputation. These precise surveys not only benefited navigation, but also revealed his scientific rigour and attention to detail, which would characterise his subsequent journeys.

In 1768, the Royal Society sought a commander for an unprecedented mission: to witness Venus’ transit across the sun from the remote island of Tahiti, a celestial occurrence critical for measuring the Earth’s distance from the Sun. Simultaneously, the Admiralty received secret orders to seek for the mysterious southern continent, Terra Australis Incognita.

Cook was promoted to lieutenant and given command of the HMS Endeavour, which set out with a crew that included renowned scientists such as botanist Joseph Banks. After successfully recording the transit in Tahiti, Cook continued south and west. He circumnavigated and charted New Zealand’s two main islands with unparalleled precision, confirming that they were not part of a larger southern mainland.

Cook continued westward until he reached Australia’s southeastern coast, which was then known as New Holland. He traversed the dangerous Great Barrier Reef, demonstrating his great sailing skills, and claimed the coast for Great Britain, dubbing it New South Wales. The Endeavour came home in 1771, carrying precious charts, specimens, and knowledge that transformed European perceptions of the Pacific.

Undeterred by the difficulties of his first trip, Cook set off on a second voyage with a reinvigorated mission: to ultimately uncover the big southern continent. Cook, commanding the HMS Resolution and assisted by the HMS Adventure, became the first navigator to cross the Antarctic Circle, according to records.

Cook’s trip, despite ice-choked seas and harsh weather, debunked the idea that Terra Australis was a habitable continent. Although he reached close to the Antarctic mainland, the harsh weather prohibited him from seeing it. Nonetheless, the journey resulted in noteworthy findings. Cook mapped many Pacific islands, including New Caledonia, the South Sandwich Islands, and South Georgia. His thorough observations improved European understanding of the region’s topography, flora, and fauna.

Crucially, Cook employed novel health techniques to battle scurvy, a common affliction of long maritime voyages. Regular provisioning of sauerkraut and citrus extracts kept his staff in excellent condition, demonstrating his dedication to their well-being and practical implementation of scientific ideas.

Cook’s final mission was to discover the fabled Northwest Passage, a passable path connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans via the Arctic. Cook, commanding the Resolution once more and accompanied by the HMS Discovery, surveyed the western shores of North America with characteristic detail, mapping from present-day Oregon to the Bering Strait.

In 1778, he became the first European to set foot on the Hawaiian Islands, which he named after the Earl of Sandwich. The expedition was warmly welcomed, and the islands provided a replenishment point for the long voyage ahead.

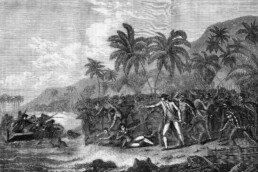

Cook was forced to retire after encountering impenetrable sea ice when crossing the Arctic Circle from the Pacific side. The ships returned to Hawaii in 1779, where tensions had risen since their first visit. A sequence of misunderstandings and rising confrontations ended on 14th February, when Cook was murdered in a skirmish at Kealakekua Bay.

Captain James Cook’s travels irrevocably altered the world map. His contributions to mapping were significant, with his maps of Newfoundland and the Pacific being the most accurate for years. Cook’s dedication to scientific discovery advanced European understanding of the Earth’s geography, peoples, and natural history.

He exemplified the Enlightenment spirit, combining curiosity and empirical observation. Cook’s expeditions gathered an unprecedented amount of data—from astronomical observations to anthropological accounts—which enhanced several fields of study. His efforts to keep the crew healthy paved the way for advances in naval medicine.

However, Cook’s legacy is not without criticism. His arrivals frequently resulted with major upheavals to indigenous societies. His investigations left a complex legacy that included illness transmission, cultural upheaval, and eventual colonial exploitation.

Today, James Cook is renowned as one of history’s greatest navigators, a man whose unwavering pursuit of discovery stretched the frontiers of the known globe. His life and voyages continue to inspire explorers and intellectuals, serving as a reminder of the human spirit’s ability to seek understanding beyond the horizon.