Stealing Churchill’s Cigar and Freezing a Moment of History

You know you’ve captured something special when your subject’s frown becomes a symbol of resolve for an entire country. That’s exactly what happened on 30th December 1941, when renowned portrait photographer Yousuf Karsh captured the iconic image of England’s indomitable wartime prime minister, Winston Churchill. This shot has become one of the most famous portraits of the twentieth century, immortalised in history books. But, like with any great event, what happened behind the scenes adds another element of fascination. Let me take you back to that time and explain what happened before and after the famed click.

Before delving into the story of that remarkable photoshoot, it’s important to learn a little bit about the man who organised it: Yousuf Karsh.

Karsh was born in Mardin, Ottoman Empire (modern-day Turkey) in 1908 and grew up in a difficult environment. His Armenian family escaped to avoid persecution during the Armenian Genocide, and he arrived in Canada as a refugee as a teenager. Fortunately, Karsh’s uncle, a photographer from Quebec, took him in and exposed him to the world of photography.

Karsh’s interest in photography grew significantly. He subsequently relocated to Boston to apprentice with John H. Garo, a renowned portrait photographer who trained him and polished his ability to capture not only faces, but the spirit of personality. When Karsh returned to Canada in the mid-1930s, he immediately established a reputation for more than just technical photography; it could portray his subjects’ inner strength, personality, and character. Karsh believed that with the right lighting and creativity, a good portrait might disclose a person’s essence.

Over the years, he photographed many notable figures, including Albert Einstein, Ernest Hemingway, Queen Elizabeth II, and Pablo Picasso. But the actual turning point in his career, his breakthrough moment, occurred when he pointed his camera at Winston Churchill.

It was December 1941, and World War II had engulfed Europe. Winston Churchill, the British Prime Minister, had travelled to Ottawa to address the Canadian Parliament, rousing support for the Allies and cementing support in the fight against the Axis forces. It was a really anxious period. Churchill had recently visited Washington, D.C., where he met with U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt to discuss post-Pearl Harbour strategy. The globe was keeping a careful eye on Churchill’s next destination, Canada.

Someone in Ottawa, aware of Karsh’s rising reputation as a photographer of influential people, arranged for him to photograph the British prime minister while he was visiting Parliament. Nobody, including Churchill, could have guessed that the ensuing photograph would capture a specific tone across the whole Allied effort.

Churchill was not too thrilled on the idea of being photographed that day. He had just delivered an important, emotionally charged address in which he guaranteed the world of Britain’s determination to continue fighting Nazi aggression. He was fatigued from the speech and didn’t want to take a photograph. However, as part of the diplomatic niceties, Churchill grudgingly consented to represent Karsh in the Speaker’s Chambers of the Canadian Parliament.

Imagine this scenario: you’ve just done one of the most important speeches of your life, you’re jet-lagged, and exhausted from constant strategic conversations — and now someone wants to flash a camera at you? It’s unsurprising that Churchill was not overjoyed. Karsh, understanding Churchill’s prominence, was understandably concerned. Not only was the prime minister losing patience, but time was running out—he only had a few fleeting moments to get this right.

Churchill was known for his love of cigars, and when he sat down, he held one of his characteristic smokes in his hand. He cut an imposing figure. Recognising that the cigar would interfere with the composition of the shot and intending to convey Churchill’s serious and determined demeanour, Karsh kindly asked Churchill if he would mind removing the cigar. No dice. Churchill, who was known for his sharp wit and occasional grumpiness, just declined and continued to ruminate, the cigar dangling from his mouth unbothered.

This is where the scene takes a dramatic change, and it may be one of the most bold actions in photographic history. Karsh performed something unexpected given his restricted options. Karsh made a brave and hazardous move by confidently approaching Churchill and, without warning, plucked the cigar right out of his mouth. It felt like time had stopped. Imagine everyone in the room gasping together. Karsh later admitted he didn’t know how Churchill would respond. The tension was palpable.

Churchill was well-known for his fiery temper. Enraged, he gave Karsh a fierce scowl, furrowing his brows deeply and pressing his lips closely together. This was one of the most defiant moments I’ve ever witnessed. But then, click ! The exact photograph that would become legendary was captured.

Karsh unwittingly captured “the roar of the lion,” a phrase commonly popularised to symbolise Churchill’s determination and resilience throughout WWII. The photograph became more than just a snapshot of a man; it also represented an unwavering nation striving for survival in the face of hardship.

Following the tremendous moment, the storm dissipated soon. As the old Churchill charm reappeared, the prime minister relaxed and let Karsh shoot several more photos of him. According to Karsh, once the cigar incident was out of Churchill’s system, he relaxed and even grinned. The follow-up images revealed a more relaxed, friendly look. However, none of those images caught the strong intent imprinted in the initial scowling image. Later, Churchill reportedly told Karsh: “You can even make a roaring lion stand still to be photographed.” Karsh’s calculated risk could have gone horribly wrong, but instead earned him Churchill’s reluctant admiration.

That one shot grew to become more than just a portrait. It was published in “Life” magazine and seen by millions of people at a time when Allied morale was desperately low. The image became a visual monument to Britain’s unwavering resolve and leadership during a difficult and uncertain period.

Karsh’s painting of Winston Churchill was recognised not only for its artistic merit, but also as a symbol of something larger: the fight against Nazism. In historical movies, classrooms, and biographies, the image serves as an everlasting memory of WWII and the leadership that propelled the Allies to triumph.

For Yousuf Karsh, the Churchill portrait was a game changer. He quickly rose to prominence as one of the world’s most sought-after photographers. His ability to capture the essence of powerful individuals became his signature. He later stated that the Churchill shot was the defining moment in his career, establishing a legacy that would last for decades.

His career extended six decades, and he photographed approximately 15,000 people, including practically everyone of importance in politics, the arts, and more. Karsh has now been credited for capturing 51 of TIME magazine’s 100 Most Influential People of the 20th Century.

Despite his prominence, Karsh was always humble. He didn’t desire power for its own reason; rather, he was genuinely interested in capturing the human spirit underlying the titles and positions. His concept was straightforward: no subject was too important or small, and everyone possessed something particularly powerful within them. And it was his responsibility to convey it to the world.

Regardless of his accomplishments, one thing was certain: the photograph of Winston Churchill was unrivalled. Capturing that moment of defiance, a man who represented the spirit of resistance in the face of overwhelming odds, cemented Yousuf Karsh’s place as a photographic legend, inextricably linked to one of the twentieth century’s most recognised leaders.

Though Karsh went on to take countless classic photos during his long and illustrious career, the photograph of Churchill remains unique. What makes it timeless isn’t just the scowl; it’s the context, the tension in the room, the world on the verge of anarchy, and a photographer willing to push his powerful subject to his breaking point.

The painting was more than just about Winston Churchill; it expressed the collective spirit of resistance and determination that pervaded the Allied nations during WWII. And in the little room where Yousuf Karsh confronted a disgruntled prime minister and flicked his cigar away, history was not only documented, but also created.

In Focus Mr President Behind Closed Doors

As America enters on a new era of leadership with Donald Trump’s re-election in the 2024 presidential election, the work of the Chief Official White House Photographer becomes increasingly important. This prestigious post has changed over decades, playing an important role in preserving both historical and human events from each government. The White House Photographer is entrusted with capturing the president’s humanity in its most candid form, allowing citizens to see beyond the podium, past the polished speeches, and into the quiet, unguarded moments that reflect both the weight of leadership and the vulnerabilities of the person holding the office.

The job of Chief Official White House Photographer was established in 1963 by President John F. Kennedy, who nominated Cecil W. Stoughton as the first to hold the title. Kennedy recognised photography’s ability to affect public opinion while also connecting people with their leaders on a personal level. This practice was carried on by subsequent presidents, each of whom brought fresh aspects of personality and leadership style to the forefront. Over time, the role became more entrenched, with photographers having unprecedented access to the president’s life, documenting everything from high-stakes discussions in the Situation Room to family moments at the White House.

The White House Photographer’s primary responsibility is to document history as it unfolds. Each administration’s photographer carries the weight of their predecessors’ legacies, from Kennedy’s optimism to Obama’s revolutionary years and beyond. As America’s next chapter begins in 2024, this function will become even more important.

While a presidency is frequently viewed through the prism of power and authority, the Chief Official White House Photographer works to highlight the president’s human side. The lens frames moments of exhaustion, joy, reflection, and friendship with empathy. This humane side bonds Americans to their leader in ways that no speech or policy can.

During Trump’s first term, Chief Official Photographer Shealah Craighead recorded a distinct blend of the president’s relentless resolve and more intimate moments, such as quiet chats with children, unguarded chuckles, and encounters with White House staff. These glances revealed a softer, more sympathetic side to a leader who was frequently seen as tough and determined.

In 2024, the Chief Official Photographer will undoubtedly face fresh obstacles and opportunities as they chronicle Trump’s return to power. With changing social and political environments, documenting the president’s humanistic side serves not just as a record-keeping tool, but also as a link between a diverse populace and the figurehead of American democracy.

The White House Photographer’s portfolio contains photos that have become part of America’s historical narrative. Perhaps one of the most iconic images was Pete Souza’s “Situation Room” photograph from 1st May 2011, taken during the Obama administration. It recorded senior officials’ nervous faces as they monitored the mission to apprehend Osama bin Laden. This image, which expressed both determination and concern, captured the gravity of presidential decision-making in real time.

Craighead got one memorable image of Trump during his previous tenure: the president sitting peacefully in the Oval Office after a long day, gazing out a rain-streaked window. The photo’s loneliness and reflection reflected a side of the president that is rarely seen—one characterised by solitude, introspection, and the constant weighing of decisions that touch millions.

As the 2024 administration takes shape, the Chief Official White House Photographer will continue to capture both the familiar symbols of power and the extremely human qualities of leadership. Whether in times of national victory, catastrophe, or quiet introspection, their images serve as a living document—a visual diary—that preserves not just the image of a president, but also the soul of the country.

Today, the post of Chief Official White House Photographer is recognised as an essential component of American democracy. Their work serves as a reminder that there is a person behind the title of “president”. As we consider the significance of the 2024 election, remember that these captured moments—some legendary, some quiet—tell our story. With each click of the shutter, the photographer creates a lasting visual imprint of America’s history.

Louis Daguerre: The Frenchman Who Gave Birth to Photography

It’s the early nineteenth century, and no one has seen a photograph yet. Paintings are still the preferred medium for capturing moments in time. Artists spend hours, if not days, working on canvases to capture a fleeting expression or a stunning landscape. Imagine the joy and astonishment that people felt when they first saw an image generated entirely by light—no brushes, no pigments, just light and chemistry. This is the world Louis Daguerre entered. His creation, the daguerreotype, irrevocably altered not only art, but also the way we see, remember, and record life.

Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre was not always obsessed with photography. Daguerre, born in 1787, grew up in the little French town of Cormeilles-en-Parisis. As a young man, he was drawn to fine arts and began his career as a painter, subsequently becoming a set designer for theatre shows in Paris. It was during these early endeavours that his passion for realistic, atmospheric effects emerged. Daguerre was well-known for his magnificently painted theatrical backdrops and involvement in scenic illusions through the Diorama, a prominent Paris attraction. The Diorama was well-known for its huge displays that employed creative lighting techniques to create the appearance of movement. Daguerre aimed to recreate reality rather than simply capture a scene. He was well positioned for what came next—he’d try to capture that beauty in a new way: photography.

Daguerre did not invent photography, but he played an important part in its early development. Enter Nicéphore Niépce, a French inventor who had been conducting his own photography experiments. Niépce invented a technique that used bitumen-coated plates to capture extremely primitive images. The process was painfully slow, and the photographs were hazy at best. However, when Niépce collaborated with Daguerre in 1829, things began to move considerably more quickly.

Niépce and Daguerre’s cooperation lasted until Niépce died in 1833. Undeterred, Daguerre continued on his own, improving the methods they had developed. His big breakthrough came when he discovered that exposing iodine-sensitized silver plates to light for a set amount of time resulted in crystal-clear images that did not fade instantly (a major drawback with earlier forms of photography).

In 1839, Daguerre introduced the world to the daguerreotype. He had worked out how to permanently hang onto a moment in time by combining silver-plated copper and sulphur fumes to “develop” the image and using a unique sealing procedure to set it in place. This was monumental.

Daguerre’s creation was unlike anything anybody had seen before. When the French government learnt about it, they realised they were dealing with something revolutionary. In August 1839, in a remarkably modern act, the French government bought the rights to Daguerre’s method and declared it a gift “free to the world.” That’s correct—they essentially invented “open-source” photography over 180 years ago!

With the method in the public domain, experimental artists, scientists, and curious minds all over the world began generating their own daguerreotypes. Photography was no longer limited to a small group of tinkerers; it was now available to anybody with access to the reasonably inexpensive supplies.

One of the most appealing aspects of the daguerreotype was its unparalleled ability to capture lifelike detail. These photographs were extremely sharp, allowing viewers to see textures and characteristics like never before in any medium. Portraits, landscapes, and cityscapes that used to take painters months to complete could now be caught in minutes. It was a technological marvel that instantly put photography on the map. Literally.

By the mid-1840s, daguerreotype studios were popping up in major cities across Europe and the United States, and photographers had become the new artists in town. It’s vital to emphasise that the process wasn’t without drawbacks. Early daguerreotype exposure times could range from 10 to fifteen minutes. To avoid blurred findings, subjects had to sit totally still. This meant that, over time, stoic expressions became a trademark of early photography—not the spontaneous, candid moments we can capture now with a mere tap on our smartphones!

Furthermore, generating a daguerreotype required meticulous effort. The plates were sensitive to chemicals and light before being exposed, so handling them properly was critical to ensuring the image was sharp and intact. The entire process was labour-intensive and required a high level of expertise.

Despite these limitations, daguerreotypes remained quite popular, particularly for portraiture. People who had never been painted before—most people couldn’t afford to commission a portrait, after all—were suddenly able to pose for a daguerreotype and have a concrete image of themselves or their loved ones. For the first time in history, the middle class gained access to something formerly held only for royalty or the ultra-privileged: a visual record.

Interestingly, Daguerre was not a particularly good photographer. While he continued to improve the daguerreotype technique, most of his popularity was based on inventing and promoting the technology rather than actually employing it.

Surprisingly, by 1850, Daguerre’s daguerreotype was already facing competition. Various new photography processes emerged, posing a challenge to the daguerreotype’s often-complicated procedure. One of the biggest disadvantages of this technology was that it produced only one, unique image. Once the exposure was made on a plate, it was over. If you wanted a different image, you would have to retake the photo. Other techniques, such as the calotype invented by William Henry Fox Talbot, established the concept of a negative that could make many prints, which was extremely significant for the future of photography.

Nonetheless, Daguerre’s significance cannot be underestimated. His method was the first to become widely accepted and commercially successful. It spanned the gap between invention and art, allowing people to embrace this new magical technology in ways that no one had imagined conceivable only a few years before.

Though the daguerreotype had gone out of favour by the 1860s, Louis Daguerre’s impact lives on in every photograph we take today. His work established the groundwork for future inventors to build upon, which is exactly what any pioneer wishes for. Photography is an important part of modern communication, art, and documentation, but it all began with a flash of light and a silver plate. From early static portraits of stern-faced sitters to the casual pictures we share on social media today, there is a direct line back to Daguerre.

So, the next time you take a smartphone photo, remember the Frenchman who was fascinated by light and reality. Consider Louis Daguerre, the man who observed the world not only with an artist’s eye, but also with a visionary’s drive. Photography, which most of us take for granted today, began as a man’s bold goal of pushing boundaries and permanently changing the way we capture time.

The Compact Camera That Changed The World

The 35mm film format transformed the field of photography by making it more accessible, portable, and innovative. This achievement dates back to the early twentieth century, and it owes much of its success to Oskar Barnack, a visionary engineer. His creativity, along with a growing desire for lightweight cameras, ushered in a new era of photography that would have a long-term impact on both professional and amateur photographers.

Prior to the introduction of 35mm film, photography was a time-consuming process. Early cameras were huge and frequently required tripods, and the film they utilised was cumbersome. Cameras were often built with glass plates or medium-format roll film, which made them bulky and difficult to transport. However, things began to change in the 1920s, when Oskar Barnack, an engineer at the Leitz firm (later known as Leica), pioneered the development of a more compact photographic equipment.

Barnack’s breakthrough idea stemmed from his unhappiness with the photographic technology available at the time. As an ardent photographer, Barnack was frequently irritated by the limits of large-format cameras. They were not only difficult to transport, but they also required long exposure periods, which made it impossible to catch moving scenes. His objective was clear: he wanted to design a camera that was portable, adaptable, and capable of shooting high-quality photographs with ease. This notion resulted in the creation of the 35mm format, a watershed moment in photography history.

Oskar Barnack’s adventure started in the early 1900s. Born in Germany in 1879, he began his career as a precision mechanic before joining Ernst Leitz Optische Werke in 1911. Barnack was tasked at Leitz with tackling a critical problem: developing a portable motion picture camera for use in the field. In 1892, Thomas Edison and William Dickson established 35mm film stock as the standard in cinema. However, Barnack saw possibilities in using the same film for still photography, which was a dramatic departure from existing camera technology.

He developed the Ur-Leica (short for “Leitz Camera”) prototype in 1913. This small camera was revolutionary since it used 35mm film, which is generally reserved for cinematic pictures. What set it apart from earlier cameras was its capacity to expose a small, exact area of the film, allowing several photos to be captured on a single roll. This led to the invention of taking numerous frames in succession, which is an important aspect in making photography both accessible and efficient.

While Barnack’s Ur-Leica prototype was completed in 1913, the outbreak of World War I postponed its further development and commercialisation. However, the framework had been established. Barnack’s innovation stemmed from his decision to employ a film format that was widely available but underutilised for still photos. The 35mm film format provided various advantages, including portability, rapid exposure, and the ability to take more photographs each roll. These characteristics were highly valued for both experts and enthusiasts looking to push the limits of their craft.

In 1925, the Leitz business officially debuted the Leica I, the first commercial 35mm camera. Its small size, combined with high-quality lenses and portability, made it an instant hit. The Leica I revolutionised the photographic profession by changing the way photographers approached their job. Instead of relying on bulky equipment and limited mobility, they could now transport a compact camera that provided tremendous creative freedom.

The 35mm film format’s adaptability was essential to its appeal. Photographers might use smaller film stock to obtain 36 exposures on a single roll. This was a significant advance over larger formats, which typically allowed only a few images before requiring film changes. The 35mm format also offered technological advantages: because the film was compact, lenses could be constructed to provide sharper resolution and greater detail, allowing photographers to produce high-quality pictures.

For photojournalists, the 35mm format was a boon. Its lightweight and small design allowed photographers to operate in situations where speed and discretion were critical. Henri Cartier-Bresson, a famed photographer and pioneer of street photography, famously employed Leica cameras to capture candid moments that would have been impossible with larger cameras in the past.

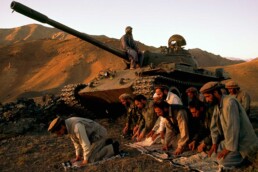

Similarly, documentary photographers preferred the 35mm format for fieldwork. Robert Capa, one of the most well-known combat photographers of the twentieth century, used his Leica to take striking, dynamic photos on the front lines of conflict. His iconic photos from the Spanish Civil War and the D-Day landings during World War II were captured with 35mm cameras, emphasising the format’s importance in documenting historical events.

While 35mm film was originally created for motion movies, it acquired popularity in still photography due to the success of Leica cameras. In the 1930s and 1940s, other camera manufacturers began to use the 35mm format, resulting in a surge in the popularity of tiny cameras. Companies including Contax, Nikon, and Canon began making models based on Barnack’s original Leica.

In addition to its influence on professional photography, the 35mm format grew popular with hobbyists and amateurs. By the mid-twentieth century, cheap 35mm cameras had enabled people from many areas of life to pursue photography as an art form. The introduction of colour film in the 1930s, followed by Kodak’s popular Kodachrome in 1935, greatly increased the possibilities of 35mm photography, making it the preferred format for both black-and-white and colour photography.

The format’s adaptability also extended to cinema. Directors and cinematographers discovered that 35mm film was an appropriate medium for producing high-quality motion pictures. From Hollywood blockbusters to smaller films, 35mm became the industry standard, requiring exact image quality and dependable film stock.

Today, the 35mm format has a unique role in both photographic history and modern practice. Although digital photography has mostly overtaken film in the twenty-first century, 35mm film is still a popular medium among photographers who value the particular look it provides. Film’s grain, colour reproduction, and dynamic range are difficult to mimic digitally, hence many photographers continue to shoot with film even in the digital age.

Furthermore, the heritage of Oskar Barnack and his pioneering work with 35mm film lives on through the continuous use of Leica cameras. Leica remains identified with precision engineering, high-quality optics, and timeless design, and its cameras are still covered by photographers who appreciate workmanship and heritage.

The 35mm film format transformed photography by making it more accessible, portable, and innovative. Oskar Barnack’s goal of developing a tiny camera that could use 35mm motion picture film changed the photographic world forever. From the launch of the Ur-Leica to the widespread use of the format by pros and hobbyists alike, 35mm film has influenced how we capture the world around us. Its legacy, in both still photography and cinema, continues to demonstrate the power of invention, inventiveness, and the pursuit of excellence in capturing life’s ephemeral moments.

Capturing Moments the Old-Fashioned Way

In an era dominated by digital technology, where quick gratification and the convenience of smartphone photography reign supreme, the resurrection of analogue cameras is both amazing and exciting. This comeback reflects a deeper cultural desire for authenticity, nostalgia, and the tactile involvement that analogue photography uniquely provides. As modern photographers and enthusiasts increasingly gravitate toward film cameras, it is vital to investigate the historical context, the reasons for this trend, and its implications for the future of photography.

The history of photography began in the early nineteenth century, when Louis Daguerre invented the daguerreotype in 1839. This pioneering approach paved the door for countless advances in photographic processes, including the invention of various types of film cameras throughout the twentieth century. In the 1920s, Leica and Nikon popularised the 35mm format, which became the norm for both professional and amateur photographers. This era saw the rise of great photographers such as Ansel Adams and Henri Cartier-Bresson, who used analogue cameras to record some of the most impactful photographs in photographic history.

However, the arrival of digital photography in the late twentieth century significantly altered the environment. Digital cameras provided the attraction of immediacy, allowing photographers to capture innumerable photos without the limitations of film. As a result, film sales began to plummet, and by the early 2000s, major film manufacturers had discontinued production of several film stocks. This move signalled the end of an era and the dawn of a new, digital-dominated era in photography.

Despite the overwhelming dominance of digital photography, a noteworthy counter-movement has formed over the last decade, marked by a renewed interest in analogue cameras and film photography. This comeback can be linked to a number of elements, including a desire for authenticity, a reaction to the disposable nature of digital photographs, and the distinct visual qualities that film offers.

In a world inundated with digital photos that are frequently altered, filtered, and edited, many photographers and consumers are looking for a more genuine form of expression. Film photography, with its naturalistic nature, conveys a sense of honesty and authenticity. Each frame contains the weight of intention as well as the medium’s unpredictable nature, resulting in a stronger connection between the photographer and their subject.

Furthermore, the tactile experience of shooting with a film camera, from loading film to manually adjusting settings, promotes a deep connection with the art form. This hands-on method contrasts dramatically with the convenience and detachment of digital photography, encouraging photographers to slow down and enjoy the process.

In today’s fast-paced environment, when photos are shared and devoured in seconds, the fleeting nature of digital photography has created a sense of disposability. Many people take thousands of photographs, yet only a few are printed or properly appreciated. This ephemerality contradicts the notion of photography as a tool of remembering and preservation.

Analogue photography, on the other hand, promotes intentional practice. Each shot on film is valuable and limited, as photographers are frequently limited to a roll of 24 or 36 exposures. This limitation encourages a focused and intentional approach, forcing people to consider composition, lighting, and subject matter before pressing the shutter.

Film photography’s inherent visual attributes help to fuel its resurgence. The grain, texture, and colour palette of different film stocks produce a distinct visual language that many photographers enjoy. Film’s faults can enrich photographs with character and passion, traits that are sometimes lost in the antiseptic accuracy of digital photography.

Many contemporary photographers have adopted this aesthetic, experimenting with various film stocks to obtain distinct appearances. For example, the warm tones of Kodak Portra 400, the brilliant colours of Fujifilm Velvia, and the great contrast of Ilford HP5 are all recognised for their distinct features. This innovation not only demonstrates film’s artistic potential, but it also connects modern photographers to the rich tradition of analogue approaches.

The resurrection of analogue photography has created a thriving community of film enthusiasts. Online platforms, social media groups, and dedicated forums let people to debate techniques, share their work, and even trade film and cameras. This sense of community strengthens the idea that analogue photography is more than just a trend, but a movement based on shared beliefs and experiences.

Workshops, meetings, and film festivals have also emerged, allowing photographers to network while also learning and collaborating. Events such as the “Film is Not Dead” festival and different film photography expos honour the medium while also providing a platform for budding artists to present their work.

Despite the increased popularity of analogue photography, numerous obstacles persist. Newcomers may face considerable difficulties due to film availability and increased processing costs. As a result, some photographers have turned to DIY processing techniques or sought out local labs that specialise in film development. However, the growing popularity of film has prompted some producers to reissue obsolete film stocks, ensuring that aficionados have a wide range of possibilities.

Furthermore, the environmental impact of film manufacturing and chemical processing raises ethical concerns. As photographers grow more aware of their environmental impact, conversations concerning sustainable methods in the analogue world are gaining steam. Initiatives aimed at reducing waste and encouraging environmentally friendly processing processes are critical to sustaining the viability of film photography as a medium.

The rebirth of analogue cameras is more than just a nostalgic yearning for the past; it reflects a significant cultural change towards authenticity, intentionality, and artistic experimentation. Photographers who appreciate the unique properties of film not only honour the medium’s rich heritage, but also contribute to its present progress.

This movement calls into question the idea that photography is solely a digital discipline, reminding us that the art form is multidimensional and ever-changing. The rebirth of analogue photography demonstrates the medium’s ongoing strength, emphasising the beauty of imperfection and the story contained within each frame. As we move forward, the blending of ancient and contemporary approaches will surely impact the future of photography, guaranteeing that digital and analogue coexist harmoniously, enhancing our visual culture for future generations.

The Unspoken Stories in the Photos of September 11

In times of great tragedy, photographs frequently speak louder than words. On a clear September morning in 2001, the world witnessed one of the most catastrophic attacks in recent memory. While news coverage and publications chronicled the day’s events, it was the famous images that permanently carved those moments in the collective memory. These photos transcended the turmoil, giving shape to emotions that appeared too tremendous to express in words. Among the dust and debris, certain images stood out—not only as evidence of destruction, but also as expressions of human tenacity, sadness, and solidarity. These photos served as anchors, allowing millions of people around the world to make sense of an otherwise unfathomable occurrence. For many, the photographs were their first exposure to the scale of the calamity, providing an emotional connection to an event that would change the twenty-first century.

During times of crisis, pictures become an indispensable medium for storytelling. They capture not only the details of an event, but also the feelings that surround it. The photographs from this sad day were no different. They acted as universal languages, crossing borders and cultures to instantaneously communicate the enormity of the event to every part of the world. From the collapsing skyscrapers to the smoke-filled skyline, each photograph appeared to stop time, capturing raw human emotion in a way that words could not.

However, these photographs become part of history rather than simply capturing it. The importance of imagery in times of tragedy, as shown during these attacks, is critical—not only for recording, but also for the emotional resonance it offers. They are more than just still images from a calamity; they are testaments to shared grief, suffering, and, finally, recovery.

Certain photos from that day became iconic, influencing how the public recalls the event. Thomas Franklin’s shot of three firefighters raising the American flag over the rubble at Ground Zero remains one of the most powerful emblems of hope and endurance. This photograph, like the famous World War II image of soldiers raising the flag at Iwo Jima, served as a reminder of the American people’s indomitable spirit.

“The Falling Man,” by Richard Drew, is another iconic shot. It depicts an unknown individual in mid-fall after leaping from one of the towers. The photograph ignited heated debates about human dignity, the nature of suffering, and how people make decisions when confronted with the unspeakable. “The Falling Man” is still one of the most disturbing images of the time, forcing viewers to confront the human cost of the calamity in an intimate, deeply personal way.

Each classic photograph tells a story—not just about the photographer, but also about the individuals captured in time within those frames. These photographs feature the faces of first responders, regular people, and unidentified casualties, offering as harsh reminders of the human beings at the heart of the tragedy. These human experiences make the actual weight of the event more tangible. For example, several of the firefighters captured at Ground Zero became heroes, their photographs representing bravery in the face of insurmountable odds. The images of individuals fleeing the collapsing skyscrapers, coated in ash, and citizens watching in despair from the streets serve as a constant reminder of the frailty and fragility of existence. However, each shot contains a silent tribute to the innumerable unsung heroes who appeared in those tumultuous times.

Photographers on the ground that day faced unprecedented hurdles. Capturing these moments required enormous courage and mental focus as the attack unfolded in real time. Photographers such as James Nachtwey, noted for his work in conflict zones, photographed the spreading mayhem while balancing the necessity to capture history with the ethical implications of documenting such severe human misery. These photographers, often at considerable personal risk, produced photos that were more than just snapshots, but historical records. Their work proved critical to the global understanding of the event, influencing how the world perceived and digested it. Each photograph presented a story that went beyond the confines of New York City, conveying the seriousness of the moment to all viewers, regardless of where they were.

The photos from that day had a global impact, shaping not just America’s but also the international community’s reaction to the catastrophe. As the photographs spread through traditional and digital media, they elicited a sense of shared empathy beyond national lines. The scenes of destruction, heroism, and sadness brought people together in their grief, making the attacks a worldwide experience rather than just an American one. The images of smoke pouring from the towers, people fleeing the streets, and first responders running towards the rubble were instantly recognised around the world. In the aftermath, these photos came to represent both fragility and resilience. They enabled the global public to engage with the event in ways that would have been unthinkable without such visual documentation.

Photographers faced ethical challenges when recording such a sensitive and tragic occasion. Editors and photographers were forced to make difficult decisions about what to show and what to keep. Balancing the public’s right to see history with the obligation to protect the victims’ dignity was an ongoing struggle. Photos like “The Falling Man,” while striking, provoked controversy about whether such intimate depictions of death should be shared with the public. This ethical tightrope walk serves as a reminder of photography’s difficult role in capturing history. It portrays reality in its most raw form while also navigating the emotional and moral ramifications of depicting suffering, particularly on such a large scale.

Following the disaster, photography continued to play an important role—not only in recalling the attacks, but also in chronicling the recovery process. Images of New York’s resiliency, ranging from the Tribute in Light to the first steps towards rebuilding the World Trade Centre, were strong emblems of hope and healing. Photos of survivors, first responders, and relatives visiting memorial locations served as reminders that life went on and that, albeit slow, healing was possible. These images have become as much a part of the event’s legacy as photographs of the attacks themselves. They represent not only loss but also rejuvenation, emphasising the resilience of the human spirit.

The significance of these classic photos continues to influence how we recall that awful day. They have been kept in museums, memorials, and history books, so that the stories they tell will never be forgotten. They serve not just as historical records, but also as lessons for the future, reminding us of the strength that comes from solidarity, even in the face of tremendous odds. As we look on the photos from that day, we are reminded of how powerful photography is in changing our view of history. These photographs continue to elicit strong emotions and will forever represent the fragility and resilience of the human soul.

Michael Yamashita: The Silk Road Reimagined Through His Eyes

Few photographers can blend the ancient and new, the antique and contemporary, like Michael Yamashita. Yamashita is a seasoned National Geographic photographer who has spent decades capturing the essence of places and cultures that influence our knowledge of the globe. His trek along the Silk Road exemplifies this passion—a journey that not only retraced the steps of traders and explorers, but also reawakened historical echoes along one of humanity’s most storied trade routes.

The Silk Road is more than a network of historic trade routes; it represents civilisations’ interdependence. For more than a millennium, it stretched from the heart of China to the Mediterranean coast, serving as a conduit for the interchange of products, ideas, and cultures. Spices, silk, gold, and other precious goods passed through this network, as did ideas, religions, and technology that would change the path of human history. As one travels along these historic roads, it becomes evident that the Silk Road was more than simply a physical route; it was a cultural artery that fuelled the rise of empires and the mingling of many peoples. Yamashita set out to depict this rich and complex history, a work that needed not just a sharp eye for detail but also a thorough study of the historical context that gives the Silk Road its significance.

Yamashita embarked on his voyage, following in the footsteps of numerous explorers, traders, and pilgrims who had travelled the Silk Road throughout history. His travels led him across a diverse range of settings, from harsh deserts in Central Asia to lush valleys in the Himalayas. Each step of the journey, he found traces of the past: ancient strongholds guarding lost routes, crumbling cities that once thrived on trade money, and religious monuments that still hold spiritual value. However, this voyage was more than merely documenting the past. It was about experiencing the present—meeting the people who live along the Silk Road now, whose lives are influenced by their forefathers’ history. Yamashita saw a living history in the busy bazaars of Kashgar, the lonely monasteries of Tibet, and the bright markets of Samarkand, where echoes of the Silk Road still affect the rhythm of daily life.

Yamashita’s vision captured the continuing spirit of the Silk Road. His shots are more than just images; they provide glimpses into a world where history and modernity coexist. Xi’an, historically the eastern terminus of the Silk Road, emerges in his art as a thriving metropolis with remnants of its illustrious past. The towering Buddha statues in the Bamiyan Valley, though damaged by time and conflict, serve as silent monuments to the cultural exchanges that occurred along these pathways. His photographs do more than simply capture the physical vestiges of the Silk Road. He captures the essence of the people who live in these areas—their tenacity, traditions, and connection to a past that continues to shape their identities. A trader in Bukhara’s marketplaces, a monk in Ladakh’s mountains, a weaver in Xinjiang’s villages—each of these people becomes mosaic of the Silk Road, bound together by the photographer’s acute eye and deep regard for his subjects.

In an age when much of the world’s attention is focused on the future, Yamashita’s art serves as a reminder of the necessity of conserving the past. His images of the Silk Road are more than just a record of what once existed; they represent an appeal to recognise the ancient network’s ongoing relevance in today’s globalised society. The Silk Road may no longer be the dominant trading route it once was, but its legacy continues to affect the modern world. The renewed interest in this route, notably through programs such as China’s Belt and Road Initiative, emphasises the long-term relevance of the linkages formed along its pathways. Yamashita’s work encourages us to evaluate how these cultural, economic, and spiritual links continue to impact our society today.

One of the most striking elements of the Silk Road is the enormous diversity of cultures it represents. As Yamashita’s trip demonstrates, diversity is not a relic of the past, but rather a current reality. The Silk Road is a melting pot of religions, traditions, and artistic manifestations, from Islamic architecture in Central Asia to Buddhist temples in China, Christian monasteries in Armenia, and Zoroastrian fire temples in Persia. Yamashita’s images capture the essence of these cultural exchanges, demonstrating how different traditions have affected and enhanced one another over time. The exquisite tilework of a Samarkand mosque, the delicate silk embroidery of a Chinese gown, and the solemn rites of a Tibetan monastery are all examples of the Silk Road’s cross-cultural contacts.

Much of the Silk Road’s historic infrastructure is in ruins, but its spirit lives on. Modern trends, such as the revitalisation of commerce networks and cultural exchanges, are reviving this old trail. Yamashita’s journey provides a unique viewpoint on this resurgence, highlighting how the Silk Road continues to serve as a conduit between East and West. In today’s interconnected globe, the Silk Road is a strong emblem of cross-cultural collaboration and understanding. Yamashita’s art reminds us that, while the world has changed, the Silk Road’s principles of openness, exchange, and respect remain as vital as ever.

The significance of Yamashita’s Silk Road voyage goes beyond the images. It’s in the way these photos encourage us to look beyond our own borders and appreciate the rich fabric of human history. Yamashita has produced a visual narrative that transcends time by retracing the footsteps of ancient travellers and capturing the continuing spirit of the Silk Road—a tale that inspires us to explore, appreciate, and cherish the different cultures that comprise our planet.

In the end, the Silk Road is more than a road; it is a voyage. Yamashita has taken us on that journey through his lens, providing a glimpse into the past while reminding us of the bonds that still bind us together. His work is a celebration of the Silk Road’s ongoing heritage, demonstrating photography’s ability to preserve history and inspire future generations.

Still Moments, Moving Stories: Photography’s Role in the Social Media Era

On World Photography Day, it is both appropriate and intriguing to reflect on photography’s revolutionary journey and the changing landscape of the digital era. Photography, an art form that has moulded our perspective of the world and our place in it, is currently at a crossroads, influenced by rapid technological innovation and social media’s broad reach. The medium, which once required a significant investment in equipment and experience, is now available to millions via smartphones and social networks, democratising visual expression and radically transforming how we interpret and exchange images.

Social media networks have undoubtedly transformed photography. With the introduction of Instagram, visual storytelling has crossed traditional barriers, reaching global audiences instantly. These platforms have evolved into virtual galleries, with each user serving as both a curator and an audience member, cultivating a culture of rapid satisfaction and ongoing participation. The simplicity of sharing photographs online has opened up new possibilities for photographers, allowing them to acquire visibility and establish communities of followers at unprecedented speed. However, this transition has created additional issues, as the sheer volume of content can sometimes eclipse the artistry behind individual photographs.

In the realm of digital images, video material has emerged as a serious competitor to still photography. Platforms such as YouTube and TikTok prioritise dynamic, moving graphics, and the trend towards video storytelling has gained significant traction. The draw of video is its capacity to express motion, emotion, and narrative in ways that a single frame may hard to capture. As a result, some may claim that photography is in danger of becoming a secondary medium, eclipsed by the more immersive experiences provided by video.

Despite these obstacles, photography maintains its distinctive force and importance. Still images have a unique ability to capture moments of calm, detail, and reflection that video cannot always match. In an age where attention spans are short and content is absorbed quickly, a single, well composed shot can have a significant impact. It provides a moment of pause, inviting viewers to connect with the image on a deeper level and consider its narrative or emotional significance.

Furthermore, the proliferation of high-quality smartphone cameras and editing software has enabled amateurs to explore photography in ways that were previously reserved for pros. This democratisation has resulted in an explosion of creativity, with amateur photographers generating amazing images that rival established techniques. The availability of photography tools fosters experimentation and invention, resulting in a thriving community in which new trends and techniques arise on a regular basis.

To ensure that photography remains relevant, it is critical to embrace and adapt to the changing technological context. Photographers can use social media to promote their work, connect with audiences, and collaborate with other creatives. Photographers may create intriguing narratives that work across multiple platforms by using multimedia components and experimenting with new formats. This technique not only preserves the art of photography, but also connects it to contemporary digital practices.

Furthermore, the integration of artificial intelligence and advanced analytics provides opportunity for photographers to hone their skills. AI-powered technologies can help you improve photographs, automate editing processes, and even create unique compositions. By using these technologies, photographers can push the boundaries of their creativity while remaining true to their vision.

The value of conventional photography abilities should not be underestimated. Mastery of composition, lighting, and skill is still required to create compelling photos. While digital tools and platforms provide new possibilities for expression, photography’s fundamental principles remain to underpin its creativity and efficacy. Preserving these abilities ensures that the soul of photography is not lost as technology advances.

As we commemorate World Photography Day, it is critical to recognise the art form’s dynamic character and enduring significance. Photography, in its numerous forms, continues to capture the essence of the human experience as well as the beauty of our surroundings. By embracing innovation while preserving traditional techniques, we can ensure that photography remains a lively and crucial medium for future generations.

In an era dominated by digital content and altering media trends, photography’s endurance stems from its capacity to adapt while retaining its distinct characteristics. Whether it’s a magnificent single frame or a dynamic multimedia production, photography provides a window through which we may investigate, comprehend, and appreciate the world. As we move forward, let us recognise photography’s rich history and its current relevance in our ever-changing digital landscape.

The Grey Canvas of Victory: Panji's Inspirational Portrait Project

In a remarkable testament to the power of vision and perseverance, Panji Indra Permana (@panjiindra)has etched his name into the annals of photographic excellence. Winning the Portrait Category at the prestigious Hasselblad Master 2023, Panji’s achievement stands as a beacon of inspiration for photographers worldwide. With a career spanning over two decades, his latest project, The Cyclist Portrait (@thecyclistportrait), has captivated the industry with its poignant exploration of cycling culture. We had the privilege to delve into Panji’s journey, uncovering the essence of his creative process and the story behind his award-winning work.

Can you start by telling us about yourself and your profession?

My name is Panji Indra Permana, and I am a professional photographer specialising in editorial and commercial photography. I embarked on my photographic journey in 2000 and began my professional career in 2003. From 2004 to 2010, I worked as an in-house photographer for a fashion magazine in the capital city. Following this, I transitioned to freelance work, contributing to various magazines and engaging in commercial projects.

What inspired you to create @thecyclistportrait, and can you tell us about its journey?

The Cyclist Portrait (TCP) began as a project during the pandemic. Witnessing the dramatic rise in cycling as a new lifestyle choice, I was inspired to document this trend. As an avid cyclist since 2010, I saw an opportunity to capture the essence of this growing movement. Initially intended as a lifestyle photography project, TCP evolved into a social campaign aimed at promoting cycling as an alternative transportation mode. It seeks to increase public awareness about cyclists and foster a ‘share the road’ mentality among all road users.

Can you share some of the influencers or role models who have significantly shaped your work and style?

For The Cyclist Portrait (TCP), I was significantly inspired by Scott Schuman, known as The Sartorialist, whose street style portraits I greatly admire. In the realm of editorial photography, the works of the late Peter Lindbergh, Paolo Roversi, and Patrick Demarchellier have been influential. Additionally, I draw inspiration from fashion photographers such as Nick Knight, Tim Walker, and the duo Mert Alas and Marcus Piggott.

Could you share the story behind your winning photos and what inspired you to create them? Why use a hanging background concept?

The photos that won the Hasselblad Master award were among the early portraits in TCP, capturing local street vendors near my home. I even photographed some vendors right in front of my house. The grey backdrop was chosen not only as a distinctive feature of TCP but also as a symbol of the urban environment. It represents the grey roads we all share, highlighting that regardless of our bicycles, we are all equal against this backdrop.

What are your plans for the future with @thecyclistportrait?

TCP plans to tour around Java, capturing portraits of street vendors and cycling communities across the island. We also hope to expand the project beyond Java and potentially publish a book to showcase the journey.

What challenges did you face with @thecyclistportrait?

Maintaining consistency in photographing street vendors has been challenging, particularly while managing commercial work. The process requires substantial time and effort, as I conduct these photo hunts while cycling and carrying all my equipment and the distinctive grey backdrop.

Among the numerous photos captured by @thecyclistportrait, which are your personal favourites and why?

One of my favourite works is the portrait of Pak Bodong, a banana vendor who recently won an award. His dedication despite his age is truly inspiring. I also enjoy supporting cycling events within the community, as they offer dynamic expressions and exciting styles.

What advice would you give to aspiring photographers who want to create inspiring artwork?

Find a personal project with a theme you are passionate about, so you can continuously enjoy the process. Remain consistent in your work, making it a routine that fosters your creativity.

Panji Indra Permana’s triumph at the Hasselblad Master 2023 is more than a personal achievement; it is a celebration of the intersection between passion and artistry. His project, The Cyclist Portrait, exemplifies how a creative vision can resonate on both a local and global scale. Through his lens, Panji captures not just images but stories, uniting people through the shared experience of cycling. As we congratulate him on this well-deserved accolade, we are reminded of the power of perseverance and the impact of personal projects in shaping the world of photography. Panji’s journey is a poignant reminder that with dedication and creativity, extraordinary achievements are within reach.

The Decisive Moments of Henri Cartier-Bresson

Henri Cartier-Bresson is one of the most revered and influential photographers in history. Cartier-Bresson, dubbed the “Father of Modern Photojournalism,” captured the essence of human experience with an amazing ability to seize the brief, decisive moments that characterise life. His photos are more than just historical documents; they are significant narratives that depict the complexities of the human condition.

Cartier-Bresson was born in Chanteloup-en-Brie, France, in 1908, and grew up in an art and culture-rich environment. His affluent family nurtured his artistic interests, prompting him to study painting. Influenced by the Surrealist movement, he developed a keen eye for the spontaneous and strange, which would later become characteristics of his photographic approach. His education and artistic interests created the groundwork for his distinct approach to photography.

Cartier-Bresson’s switch from painting to photography occurred after he encountered a shot by Martin Munkácsi that had a tremendous impression on him. This snapshot depicted boys racing into the surf of Lake Tanganyika, portrayed with a spontaneity and vibrancy that art could not replicate. Cartier-Bresson was inspired to buy his first Leica camera, which allowed him to explore the world with an unobtrusive lens while capturing candid moments with precision.

Cartier-Bresson co-founded Magnum Photos in 1947 with legendary photographers Robert Capa and David Seymour. This cooperative agency revolutionised photojournalism by giving photographers the freedom to capture stories as they saw fit. Magnum’s cooperative culture mirrored Cartier-Bresson’s conviction in the purity and authenticity of visual narrative. His work at Magnum cemented his status as a prominent figure in the field.

One of the most distinguishing features of Cartier-Bresson’s work is the concept of “The Decisive Moment,” which is drawn from the French “Images à la Sauvette.” This theory focused on capturing the exact moment when a scene’s visual and emotional elements came together to form a striking image. His photograph “Behind the Gare Saint-Lazare” shows this, with a man leaping over a puddle and his reflection caught in perfect symmetry, symbolising the transient yet eternal aspect of time.

Cartier-Bresson’s photographic style was distinguished by his excellent use of composition, lighting, and candid photographs. He eschewed using flash and frequently shot in black and white, feeling that these decisions retained the sincerity of the event. His Surrealist upbringing inspired his attention on spontaneity, as he captured scenes that showed deeper truths about human nature and social structures.

His Leica camera was more than just a tool; it was a reflection of his artistic vision. Its small size and quiet operation enabled him to glide unnoticed among crowds, capturing candid moments that provided genuine insights into his subjects’ life. This method was critical in his capacity to capture key historical events and social developments.

From the Spanish Civil War to the liberation of Paris and the advent of Communism in China, Cartier-Bresson’s lens captured important moments in the twentieth century. His ability to be at the right place at the right moment, along with his compositional skills, produced photographs that are both historically significant and artistically deep. His portraits, including one of Mahatma Gandhi taken soon before his assassination, caught not only the likeness but also the spirit of his subjects, making them timeless.

Although he returned to painting in his later years, his effect on photography remained strong. His efforts were appreciated around the world, and he received various medals and honours for them. His significant books and exhibitions have continued to inspire and teach future generations of photographers, keeping his techniques and attitude current.

When considering Cartier-Bresson’s contributions, it is apparent that his legacy goes beyond his individual photos. He pioneered a new method of viewing and documenting the world, combining art and journalism to create images that reflect the universality of human experience. His work with Magnum Photos set a new benchmark for ethical and powerful reportage. Henri Cartier-Bresson’s legacy has had a great impact not only on the area of photography, but also on the broader notion of visual narrative and cultural documentation. His ability to capture the decisive moment has left an everlasting effect on the art of photography, cementing his status as one of the medium’s most influential figures.