Celebrating Galungan Through the Artistry of Penjor

As the sun rises over the lush landscapes of Bali, the island awakens to a vibrant celebration known as Galungan. This festive occasion, which occurs every 210 days in the Balinese calendar, marks the triumph of dharma (goodness) over adharma (evil) and is a time for families to honor their ancestors. Central to this celebration is the penjor, an elaborately decorated bamboo pole that stands as a symbol of prosperity and spirituality. Erected outside homes and temples, these towering structures not only add to the island’s picturesque scenery but also encapsulate deep cultural meanings, drawing visitors and locals alike into a world where artistry meets tradition.

The penjor is characterized by its graceful curve, often reaching several meters in height. Traditionally crafted from bamboo, these poles are adorned with a variety of decorations, including coconut fronds, flowers, fruits, and even small offerings. The design elements of the penjor are rich in symbolism; for instance, the upward curve represents the ascent towards the divine, while the decorative motifs reflect the abundance of nature. Each penjor is unique, with its creator imbuing personal touches that may include intricate carvings or specific colors, each of which can have its own significance. The process of creating a penjor is a communal effort, involving family members and neighbors who come together to contribute their skills, reinforcing social bonds within the community.

Beyond their aesthetic appeal, the penjor serves as a visual narrative of Balinese spirituality. The decorations often feature representations of gods, ancestral spirits, and natural elements, all of which are integral to Balinese Hindu beliefs. For example, the use of white and yellow flowers signifies purity and spirituality, while fruits symbolize abundance and fertility. As families prepare their penjor, they engage in a form of storytelling, weaving together their hopes and prayers for the future. This ritualistic aspect of penjor creation not only deepens its significance but also connects the past, present, and future of Balinese culture, offering a glimpse into the island’s rich spiritual tapestry.

The erection of penjor occurs a day before Galungan, transforming the streets and villages into vibrant corridors of color and life. As families place their penjor in front of their homes, the bamboo poles become a source of pride and joy, reflecting the hard work and creativity of their makers. The sight of these towering structures swaying gently in the breeze against the backdrop of Bali’s verdant landscapes is a spectacle to behold. It is a time when the island’s cultural heritage is on full display, inviting both residents and visitors to appreciate the beauty and meaning behind this age-old tradition.

The significance of penjor extends beyond aesthetics; it embodies the Balinese worldview that intertwines the natural and spiritual realms. The decorations often include symbolic offerings placed at the base, intended to invite blessings from the gods and ancestors. This practice underscores the importance of gratitude and respect for the forces that shape daily life in Bali. Each penjor thus acts as a conduit between the earthly and divine, reminding the community of their responsibilities toward nature and spirituality. This relationship between art and spirituality encapsulates the essence of Balinese culture, highlighting a unique perspective where every element in their environment carries meaning.

As Galungan unfolds, the atmosphere is filled with festive rituals, delicious foods, and the laughter of families reuniting. The penjor stands tall as a witness to these celebrations, a symbol of hope and abundance that transcends generations. The tradition of erecting these bamboo poles not only enhances the visual landscape of Bali but also serves as a reminder of the importance of community, spirituality, and cultural continuity. As visitors admire the penjor during this festive period, they are encouraged to reflect on the stories and meanings behind these magnificent creations, understanding that each pole represents not just artistry but also a vibrant cultural identity that is cherished by the Balinese people.

In conclusion, the tradition of erecting penjor during Galungan is a visual and spiritual celebration that embodies the essence of Balinese culture. Through their intricate designs and communal creation process, these bamboo poles connect the past and present, illustrating the enduring legacy of this island’s rich heritage. As Bali continues to enchant the world with its breathtaking landscapes and profound traditions, the penjor remains a timeless symbol of the island’s spirit, inviting all to partake in the celebration of life, culture, and community. This Galungan, let us honor the beauty and significance of penjor, embracing the stories woven into each bamboo pole and celebrating the vibrant of Balinese culture.

Cultural and Technological Exchanges on the Silk Road

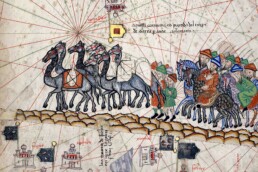

For more than a millennium, the Silk Road, a historic network of trade routes, was the principal artery connecting Eastern and Western civilisations. This extensive network of overland and maritime routes stretched from China to the Mediterranean, facilitating not only the trade of products but also the movement of ideas, technologies, and cultures. For adventurers like as Marco Polo, the Silk Road led to faraway regions and new opportunities. This article delves into the Silk Road’s origins, significance, and long-term impact, building on the story of Polo’s journeys and the larger historical environment in which they took place.

The Silk Road dates back to the Han Dynasty of China (206 BCE-220 CE), when demand for Chinese silk in the Roman Empire prompted the establishment of a long-distance trade network. Emperor Wu of Han is typically attributed for expanding these early routes that connected China to Central Asia, Persia, and the Roman Empire’s eastern provinces. Although silk was the most well-known item, other goods including as spices, precious metals, ivory, and ceramics were traded along the route, making it an important commercial lifeline.

The Silk Road, however, had far-reaching consequences beyond trade. The movement of people along these routes also permitted the interchange of knowledge, religious beliefs, and technologies, changing both Eastern and Western cultures. The Silk Road played an important role in cultural and technological dispersion, from the spread of Buddhism into China to the transfer of Chinese papermaking to the Islamic world.

By the time Marco Polo set out on his journey in the 13th century, the Silk Road had undergone periods of both prosperity and decline. The establishment of the Mongol Empire under Genghis Khan and his descendants, particularly Kublai Khan, revitalised the network, making long-distance trade more secure and efficient. The Mongols built a large empire that stretched from Eastern Europe to China, bringing together the provinces that covered much of the Silk Road under a single administrative and military organisation.

The Pax Mongolica, or “Mongol Peace,” guaranteed the safety of commerce and travellers throughout the empire’s enormous territory. This improved security was essential in permitting Marco Polo’s journeys throughout Asia. Merchants, diplomats, and missionaries travelled freely along the route, encouraged by Mongol monarchs who regarded trade as critical to their empire’s development. For the first time in millennia, East and West were linked via a somewhat stable and well-maintained commerce network.

Silk, like the route’s namesake, was one of the most sought-after products trafficked from China to the West. However, many additional items passed over the Silk Road, enriching the economies and cultures of the regions it linked. Chinese china, tea, and jade were in high demand in the West, while Central Asian horses, Indian spices, and Persian carpets were popular in the East. Luxury things such as diamonds, perfumes, and textiles coexisted with more utilitarian goods such as grain, animals, and salt.

Beyond material items, the Silk Road promoted the flow of ideas and innovations. One of the most significant examples is the spread of Buddhism from India to Central Asia and China via the efforts of monks travelling down the Silk Road. Similarly, Islamic academics who brought manuscripts and information from the Middle East contributed new scientific and mathematical notions to China. Papermaking and gunpowder, which were developed in China, spread westward and transformed society as they arrived in Europe.

Marco Polo’s travels over the Silk Road is probably one of the best-documented stories of this huge network in the 13th century. He travelled with his father and uncle from Venice to Kublai Khan’s palace, passing through several of the Silk Road’s crucial districts. Polo’s descriptions of his travels to Persia, Central Asia, and China provide unique insight into the dynamics of trade and cultural interchange along these routes.

Polo’s works reflect on the different peoples and cultures he encountered. Polo’s story takes us from bustling market cities in Persia to the vast steppes of Central Asia, capturing the essence of the Silk Road. He observed the vast magnitude of trade at markets, where merchants bartered for everything from silk to spices, and he described the sophisticated caravanserais, or roadside inns, that dot the route, providing traders with shelter and relaxation.

Polo also noticed how local monarchs facilitated trade. Many cities along the Silk Road served as cosmopolitan hubs, allowing merchants from various cultures, religions, and regions to trade commodities and ideas. The Mongol administration was crucial in guaranteeing the safety and effectiveness of trade, frequently providing protection for caravans and maintaining infrastructure. This technique enabled Marco Polo and others to travel long distances, contributing to the wealth and prosperity of the regions linked by the Silk Road.

By the late 14th and early 15th centuries, the Silk Road had begun to collapse. The decline of the Mongol Empire and the emergence of maritime trade routes, particularly those controlled by European countries, diminished the significance of overland routes. Explorers such as Vasco da Gama discovered sea routes to India and China, which pushed world trade away from the Silk Road since seaborne trade was faster and cheaper.

Despite its collapse, the Silk Road left a significant legacy. It was more than just a conduit for goods; it served as a global hub for human contact and exchange. The trading routes facilitated the spread of faiths, philosophies, art, and technologies, many of which would influence the evolution of civilisations in Asia, Europe, and the Middle East. The Silk Road also left an indelible cultural mark, affecting everything from language and architecture to cuisine and dress in the countries it united.

In modern times, efforts to resurrect the spirit of the Silk Road have emerged, particularly through programs such as China’s Belt and Road Initiative, which aims to connect Asia, Europe, and Africa via infrastructure and trade. This modern rendition of the ancient Silk Road emphasises its continuing importance as a symbol of global interconnectedness.

The Silk Road was more than just a commercial route; it was a link between civilisations, uniting them via business, culture, and knowledge. For adventurers like Marco Polo, it was a means of discovery, expanding horizons and strengthening understanding between East and West. Its past is one of collaboration and interchange, and its legacy still shapes our world today. As modern projects aim to restore its essence, the Silk Road serves as a poignant reminder of human history’s interdependence.

Rise At 10 ? Bending The Time in Xinjiang

Xinjiang, located in China’s far northwestern region, is a unique case study in timekeeping due to its geographical immensity and historical significance. Officially, the region uses China Standard Time (CST), which is UTC+8. Despite Xinjiang’s extensive longitudinal reach across multiple time zones, this time zone is consistent with Beijing’s. The reason for centralised timekeeping stems from the Chinese government’s efforts to establish administrative coherence and national unity. However, the implementation of CST in Xinjiang has resulted in a significant disparity between the official time and the region’s solar time, which has practical ramifications for daily life in this diverse territory.

Historically, the transition to CST in Xinjiang took place during a period of considerable national reform in the early twentieth century. Prior to this adjustment, Xinjiang used its own local time zones that were more closely linked with the region’s solar position. The transition to CST was part of a larger goal to incorporate Xinjiang into the national framework, reflecting the central government’s intention to streamline administrative operations and strengthen national unity. Despite this change, practical realities on the ground have forced many residents to continue using “local time,” which can diverge from official time by up to two hours. This disparity demonstrates the region’s distinct physical and cultural traits, which continue to affect local time traditions.

In everyday life, the gap between official and local solar time generates a unique dynamic in Xinjiang. Many organisations, including companies, schools, and government offices, operate on a schedule that corresponds to the region’s natural daylight rhythms rather than rigidly following to CST. As a result, daily activities in Xinjiang frequently begin and end later than what is expected according to official time. This change in local time patterns is a practical reaction to the region’s wide longitudinal range and changing daylight hours throughout the year. Travellers and expatriates visiting Xinjiang commonly need to adjust their plans to accommodate local time norms, highlighting the practical constraints and intricacies of time management in this unique context.

The time difference has an impact on many aspects of life in Xinjiang. Agriculture, a key component of the region’s economy, is one sector where the time difference has a practical impact. Farmers in Xinjiang frequently start their work sooner or later than the official hour to take use of natural daylight, increasing output and matching their activities with changing lighting conditions. Furthermore, media and television schedules in the region frequently take a hybrid approach, balancing CST with local time preferences to meet the different needs of the populace. This complex approach to timekeeping displays Xinjiang’s systems’ adaptability to meet both national and local requirements.

Furthermore, the time difference in Xinjiang is not just a technical issue; it also reflects larger sociopolitical tensions. The region’s ethnic diversity and complicated historical heritage contribute to a range of views on the official time zone. While the central government enforces CST as a symbol of national unity and administrative consistency, local communities frequently keep their own time practices as a means of cultural expression and practical adaptation. This interplay between official time and local adaptation exposes the larger issues of governance and identity in Xinjiang, demonstrating how timekeeping methods may reflect and alter cultural and political realities.

In conclusion, the time difference in Xinjiang is a complicated phenomenon that combines historical trends with modern administrative methods. Although the region officially follows China Standard Time, practical realities and local modifications provide a more complicated picture of timekeeping in this vast and diverse territory. This one-of-a-kind circumstance highlights the greater issues of managing time across diverse geographic and cultural landscapes, highlighting the delicate balance between national uniformity and local flexibility in an area with significant historical and geopolitical importance.

The Evolution of Mooncake Traditions from Ancient China to Today

The Mooncake Festival, also known as the Mid-Autumn Festival, is one of the most important cultural festivities in East Asia. This celebration, held on the 15th day of the eighth lunar month, historically symbolises the end of the harvest season and the autumn equinox. The event dates back nearly 3,000 years to ancient China, where it was first celebrated as a harvest festival in honour of the moon’s plentiful light. This time of year was chosen for the clear skies and full moon, which lighted the night and represented prosperity and harmony. Today, the celebration is a monument to the rich tapestry of Chinese culture, as well as its deep respect for the natural cycles of life.

The mooncake, a spherical pastry with a rich, sweet or savoury filling, is crucial to the event because it represents unification and wholeness. Mooncakes have been utilised in a variety of religious rites and offerings since the Tang Dynasty (618-907 AD). During this time, cakes were frequently decorated with intricate designs and loaded with ingredients such as lotus seed paste and salted egg yolks, which were thought to bring good luck. By the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), mooncakes had become an essential feature of the holiday, with their round shape representing the full moon and family reunion. Mooncake designs frequently incorporate elements of Chinese mythology, such as detailed portrayals of Chang’e, the Moon Goddess, who appears in numerous Mid-Autumn stories.

One of the most well-known Mooncake Festival legends is that of Hou Yi and Chang’e. According to tradition, Hou Yi, a talented archer, was tasked with rescuing humanity from the burning heat of ten suns that had emerged in the sky. Hou Yi used his great skill to shoot down nine suns, restoring global equilibrium and sparing the planet from destruction. As a reward for his bravery, he received an elixir of immortality. To prevent the elixir from falling into the wrong hands, Hou Yi’s wife, Chang’e, drank the potion and ascended to the moon. There, she lives as a deity, representing sacrifice and devotion. This story not only emphasises the festival’s relationship to lunar worship, but it also explores themes of selflessness and the enduring bond between husband and wife.

The Mooncake Festival is also distinguished by a number of traditional practices and regional variants. In locations like as Hong Kong, the event is celebrated with flamboyant parades, lion and dragon dances, and colourful lantern displays that illuminate the night sky. These celebrations embody the community spirit and excitement that define the festival. In Taiwan, the event is marked with dragon dances and folk performances that encapsulate the essence of traditional Taiwanese culture. In contrast, in mainland China, families often assemble for a supper, eat mooncakes, and admire the full moon’s splendour. This community part of the celebration promotes a sense of belonging and cultural continuity, helping people to reconnect with their heritage and familial roots.

In addition to ancient activities, the Mooncake Festival has grown to incorporate contemporary ideas and worldwide influences. In recent years, new mooncake varieties have evolved, using a wide range of ingredients and flavours that suit current tastes. These include mooncakes with custard, green tea, and even ice cream fillings, which appeal to a broader audience while also modernising an age-old ritual. The festival’s popularity has expanded beyond its ancestral country, with celebrations now taking place in countries all over the world. Local Chinese communities in places such as New York, San Francisco, and Toronto organise events to promote the festival’s rich traditions to a wider audience. These celebrations frequently include cultural performances, mooncake tastings, and educational activities that emphasise the festival’s significance and historical background, encouraging cross-cultural understanding and respect.

The Mooncake Festival also provides an opportunity for charitable activities and community service. Various organisations and local communities utilise the festival as an occasion to give back by organising charity events and collecting donations to help people in need. This part of the festival symbolises the virtues of generosity and compassion that underpin its celebration. To summarise, the Mooncake Festival is a lively and diverse festival rich in history, culture, and custom. It began as a harvest festival and has grown into a larger celebration of unity, family, and cultural history. Through the timeless emblem of the mooncake and the rich legends that surround it, the festival provides a fascinating view into the values and beliefs that have defined East Asian societies for generations. The Mooncake Festival, which is still celebrated both in its ancestral country and overseas, serves as a striking reminder of cultural traditions’ enduring heritage and ability to bring people together across time and place.

Marco Polo’s Glimpse into Samarkand’s Opulence

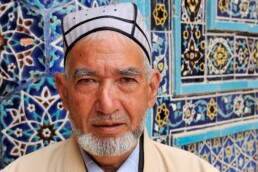

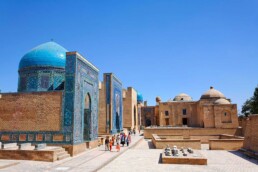

Samarkand, located in the heart of Central Asia, is a timeless testimony to the magnificence of the Silk Road. This historic city, with its sumptuous architecture and rich cultural tapestry, was once a gleaming diamond at the centre of one of history’s most important trade routes. Imagine a place where merchants’ footsteps mix with poets’ whispers, and every cobblestone tells a story. Samarkand, built over 2,700 years ago, flourished as a critical hub, connecting the East and West in a complex web of trade and culture. Its appeal drew not just commerce, but also explorers such as Marco Polo, whose descriptions of the city’s splendour captured Europe’s imagination.

Samarkand’s history is a tapestry of several influences and dynasties. It began as a fortified hamlet and flourished under the Persian Achaemenid Empire. However, it was under Alexander the Great that Samarkand began to develop into a prominent metropolitan centre. Following Alexander’s conquest, the city fell under the sovereignty of the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom, which left an indelible mark on its cultural and architectural landscape. As ages passed, the city saw the rise and fall of several empires, notably the Sassanian and Kushan, each adding to its illustrious history. However, it was during the reign of the Timurid Empire in the 14th and 15th centuries that Samarkand achieved its pinnacle of glory.

Timur (Tamerlane) created the Timurid dynasty, which helped shape Samarkand’s famous skyline. Timur, a visionary conqueror, aimed to build his capital into a magnificent centre of art and scholarship. Under his sponsorship, Samarkand thrived as a cultural and intellectual centre. This era was highlighted by the construction of great buildings such as Registan Square, Bibi-Khanym Mosque, and the Shah-i-Zinda Necropolis. These architectural wonders, complete with elaborate tilework and massive domes, represent the pinnacle of Islamic art and architecture. The Registan Square, with its three large madrasahs—Ulugh Beg Madrasah, Sher-Dor Madrasah, and Tillya-Kori Madrasah—is a spectacular reminder of Timur’s ambition and the city’s historical significance.

Marco Polo’s visit to Samarkand in the late 13th century offers an intriguing peek into the city’s thriving existence during its golden age. Polo, the Venetian traveler whose writings sparked European interest in the Far East, rated Samarkand as one of the most magnificent cities he had ever seen. His comprehensive observations of the city’s richness, busy bazaars, and sophisticated urban layout piqued the interest of mediaeval Europe. Polo’s descriptions, while often overstated, captured the city’s significance as a melting pot of cultures and ideas. His reports added to the mystique and appeal of Samarkand, enticing future explorers and traders to go along the Silk Road.

Samarkand’s strategic location at the crossroads of trade routes transformed it into a cultural melting pot, allowing for a vigorous movement of goods, ideas, and technologies. The city’s markets were famous for their diversity and wealth, selling everything from silk and spices to precious metals and diamonds. The Silk Road’s importance in promoting cultural interaction cannot be emphasised; Samarkand thrived as a hub of commerce and creativity. The city’s diversified population, which included traders, scholars, and artisans from all over Asia and Europe, contributed to its vibrant and international culture. This cross-cultural interaction enriched Samarkand, turning it into a symbol of cultural harmony and intellectual growth.

In the present period, Samarkand is a symbol of historical continuity and cultural richness. The city has made major restoration efforts to protect its architectural marvels and historical landmarks. UNESCO recognised Samarkand’s importance by designating it a World Heritage Site, guaranteeing that its rich heritage is preserved for future generations. Visitors to Samarkand may now experience the relics of its glorious past by walking through the ancient streets and admiring the majesty of its historical structures. The city’s lasting appeal and historical significance highlight the Silk Road’s role in forging the cultural and commercial exchanges that constituted human civilisation.

Samarkand’s tale is one of perseverance and magnificence, echoing the larger story of the Silk Road. Its evolution from a walled village to a great imperial city highlights its critical role in the exchange of cultures and ideas. As we follow in the footsteps of Marco Polo and other travellers who marvelled at Samarkand’s splendour, we obtain a better understanding of its historical significance. The city exemplifies the Silk Road’s continuing heritage of exploration, trade, and cultural interaction.

Retracing Marco Polo's Steps Through Asia and the Mongol Kingdoms

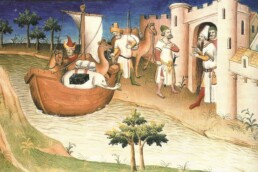

Marco Polo, a Venetian merchant and traveler, is one of the most well-known personalities in the history of travel. His epic expedition throughout Asia, which lasted over two decades, introduced the Western world to the remote reaches of the East in the late 13th century. His vivid observations of the Mongol Empire, its culture, and the riches of the Orient have left a lasting impression. This article explores the roots of Marco Polo’s travels, the historical setting, and his personal experiences, with a focus on his interactions with the Mongol Empire.

Marco Polo was born in 1254 in Venice, a thriving maritime republic of the period. Marco’s family, including his father Niccolò and uncle Maffeo, were experienced merchants who had already travelled to the East, paving the way for his own voyages. Niccolò and Maffeo travelled to the Mongol Emperor’s court in China after visiting Constantinople. In 1269, they returned to Venice and told stories of their journeys. Their contact with Kublai Khan, who displayed an interest in learning more about Western culture and Christianity, prompted them to embark on a second expedition in 1271, this time with little Marco.

At the time, Europe knew nothing about civilisations elsewhere than the Mediterranean. The East, particularly China, was a remote and largely unknown continent. Although trade routes such as the Silk Road had been established, few Europeans had journeyed far into Asia. Marco Polo’s expedition would influence not just his own life, but also European conceptions of Asia.

The late thirteenth century saw substantial political and economic development in both Europe and Asia. The Mongol Empire, commanded by Kublai Khan, ruled a huge realm extending from Eastern Europe to the Sea of Japan, including much of Central Asia and China. This unparalleled empire created safer trade routes across Asia, including the Silk Road, which allowed for the flow of products, ideas, and culture.

At the same time, Europe was transitioning from a feudal framework, and merchant families like the Polos were beginning to look for new trading prospects. The draw of the East, with its fabled riches of silk, spices, and precious metals, inspired traders to push the bounds of discovery. For Marco Polo, this expedition was about economic opportunity as much as curiosity and adventure.

In 1271, Marco, Niccolò, and Maffeo travelled from Venice by sea to the eastern Mediterranean and then on land across the Middle East. They travelled down the Silk Road, passing via Armenia, Persia (modern-day Iran), and Afghanistan. Their trek was perilous, with rough terrain, terrible weather, and a continual threat from bandits. However, the Polo family was well-prepared, having navigated the difficulties of local politics and developed alliances with numerous monarchs along the way.

It took them almost three years to reach Kublai Khan’s court in Shangdu (Xanadu), a summer palace near modern-day Beijing. This was a watershed moment for young Marco Polo, who was only 21 years old at the time. Kublai Khan was delighted by these Western visitors and warmly welcomed the Polos, particularly Marco, who rapidly piqued the Khan’s interest with his intelligence, curiosity, and ability to study languages.

Marco Polo’s stay at Kublai Khan’s court is one of the most fascinating elements of his travels. He became the emperor’s close confidant, working as a diplomat and messenger for the Mongol court. The Khan dispatched Marco on numerous missions around his kingdom, allowing the Venetian to see the breadth and diversity of the Mongol territories firsthand.

Polo’s tales describe Kublai Khan’s court as enormously wealthy and sophisticated. He marvelled at the usage of paper money, which was unheard of in Europe at the time, as well as the advanced infrastructure, like as roads and postal networks, that permitted communication throughout the enormous empire. Marco also noticed the Mongols’ religious tolerance, in which diverse faiths coexisted happily under their authority.

Marco Polo was highly astonished not just by the Mongol Empire’s riches and might, but also by the cultural distinctions. He documented the attire, habits, and lives of the individuals he met, ranging from nomadic tribes in Central Asia to highly organised Chinese culture. His thorough observations provided a unique view into the daily lives of those living under Mongol control.

After 17 years of service to Kublai Khan, Marco Polo and his family voiced a wish to return to Venice. Kublai Khan, who was already ageing, grudgingly gave them permission to leave, giving them with one final mission: to accompany a Mongol princess to Persia. Following completion of this duty, the Polos returned to Europe, arriving in Venice in 1295 after a 24-year journey.

When Marco Polo returned, he found himself in a drastically changed Venice, which was embroiled in battle with the neighbouring city-state of Genoa. Marco was arrested and imprisoned shortly after returning from war. During his time in prison, he encountered Rustichello da Pisa, to whom he dictated stories about his adventures. These anecdotes were collected in the famous book *The Travels of Marco Polo*, also known as *Il Milione*.

Despite some contemporaries’ scepticism, Polo’s writings became highly popular, serving as one of the earliest thorough portrayals of Asia available to the Western world. His evocative descriptions of the East’s richness, civilisations, and technologies impacted subsequent generations of explorers, notably Christopher Columbus, who took a copy of Polo’s book on his own expeditions.

Marco Polo’s journey to Asia is a fascinating story of exploration, diplomacy, and cultural interaction. His encounters with the Mongol Empire, in particular, show a moment in history when East and West were linked in ways that shaped the path of world history. Polo’s observations provided essential knowledge about the world beyond Europe, igniting curiosity and encouraging future adventures. Today, his legacy lives on not only via his writings, but also through an enduring fascination with the cultures he visited and the paths he took.

Onam Unfolded as a Journey Through Kerala’s Most Enchanting Festival

In the lush and lively state of Kerala, Onam is more than just a festival; it is a spectacular celebration that echoes the region’s historic traditions and diverse cultural fabric. Onam, which is strongly rooted in mythology and the agrarian culture of Kerala, signifies a time of solidarity and cultural regeneration, bringing people together to celebrate their heritage and delight.

Onam’s origins are intertwined with the mythology of King Mahabali, a respected sovereign whose story is fundamental to the festival. According to legend, Mahabali, a demon king noted for his kind and benevolent rule, received a divine boon to visit his followers once a year. His reign was characterised by prosperity and equality, and his return from the underworld to Kerala is commemorated as a moment when the earth thrives and harmony reigns. This legendary tale gives Onam a sense of historical continuity and reverence, connecting the past and the present in a celebration with significant cultural significance.

The celebration lasts ten days, with each day bringing its own set of ceremonies and traditions, culminating in the most respected day, Thiruvonam. The festivities begin with Atham, who sets the stage for a variety of festive activities leading up to the great finale. One of the most noticeable aspects of Onam is the production of Pookalam, elaborate floral arrangements that adorn houses and public spaces. These beautiful creations, composed of a variety of colourful flowers, are more than just decorations; they represent the welcoming spirit of Onam, showing the community’s joy and veneration for the returning king.

At the core of the celebrations is the Onam Sadhya, an extravagant feast that highlights Kerala’s gastronomic diversity. Served on a banana leaf, this traditional supper is a gastronomic feast that includes a range of vegetarian meals made with fresh, local ingredients. Each dish, from the acidic sambars to the sweet payasams, reflects Kerala’s agricultural abundance and culinary heritage. The Sadhya is more than simply a sensory feast; it is a community experience that draws people together around a shared table to emphasise the principles of hospitality and abundance.

The event is particularly known for its colourful folk dances and traditional games, which add to the celebrations’ intensity and enthusiasm. Kathakali, a classical dance theatre, is a festival highlight, with lavish costumes and emotive performances based on Hindu epic stories. Pulikali, also known as the tiger dance, comprises artists dressed as tigers and leopards who conduct violent dance routines representing the triumph of good over evil. These performances, combined with the exhilarating Vallam Kali or boat races, reflect the essence of Onam’s communal spirit and creative legacy, presenting a vivid representation of Kerala’s cultural richness.

In modern times, Onam has evolved while maintaining its ancient roots. The event currently includes modern aspects that reflect the changing nature of cultural practices while retaining its historical essence. This blend of history and modernity appeals to Keralites both within the state and around the world, instilling a sense of belonging to their heritage and generating a shared cultural experience that transcends geographical limits.

Onam also has a big impact on Kerala’s tourism industry, attracting travellers from near and far to see its vivid festivities. The festival’s splendour, from the intricate floral arrangements to the thrilling boat races, provides an enthralling peek into Kerala’s cultural heritage. Major activities, like as the Thrikkakara Temple celebrations and the legendary Vallam Kali, draw massive audiences, demonstrating the festival’s lasting popularity and capacity to bring people together in joy.

Finally, Onam is more than just a holiday; it is a celebration of community, wealth, and environmental stewardship. It brings together diverse cultures while reflecting the traditional ideals of equality and thankfulness. Onam, with its rich of rituals and cultural expressions, embodies Kerala’s vivid heritage and the continuing spirit of its people, providing a living celebration of history and culture that continues to inspire and unify.

The Unspoken Stories in the Photos of September 11

In times of great tragedy, photographs frequently speak louder than words. On a clear September morning in 2001, the world witnessed one of the most catastrophic attacks in recent memory. While news coverage and publications chronicled the day’s events, it was the famous images that permanently carved those moments in the collective memory. These photos transcended the turmoil, giving shape to emotions that appeared too tremendous to express in words. Among the dust and debris, certain images stood out—not only as evidence of destruction, but also as expressions of human tenacity, sadness, and solidarity. These photos served as anchors, allowing millions of people around the world to make sense of an otherwise unfathomable occurrence. For many, the photographs were their first exposure to the scale of the calamity, providing an emotional connection to an event that would change the twenty-first century.

During times of crisis, pictures become an indispensable medium for storytelling. They capture not only the details of an event, but also the feelings that surround it. The photographs from this sad day were no different. They acted as universal languages, crossing borders and cultures to instantaneously communicate the enormity of the event to every part of the world. From the collapsing skyscrapers to the smoke-filled skyline, each photograph appeared to stop time, capturing raw human emotion in a way that words could not.

However, these photographs become part of history rather than simply capturing it. The importance of imagery in times of tragedy, as shown during these attacks, is critical—not only for recording, but also for the emotional resonance it offers. They are more than just still images from a calamity; they are testaments to shared grief, suffering, and, finally, recovery.

Certain photos from that day became iconic, influencing how the public recalls the event. Thomas Franklin’s shot of three firefighters raising the American flag over the rubble at Ground Zero remains one of the most powerful emblems of hope and endurance. This photograph, like the famous World War II image of soldiers raising the flag at Iwo Jima, served as a reminder of the American people’s indomitable spirit.

“The Falling Man,” by Richard Drew, is another iconic shot. It depicts an unknown individual in mid-fall after leaping from one of the towers. The photograph ignited heated debates about human dignity, the nature of suffering, and how people make decisions when confronted with the unspeakable. “The Falling Man” is still one of the most disturbing images of the time, forcing viewers to confront the human cost of the calamity in an intimate, deeply personal way.

Each classic photograph tells a story—not just about the photographer, but also about the individuals captured in time within those frames. These photographs feature the faces of first responders, regular people, and unidentified casualties, offering as harsh reminders of the human beings at the heart of the tragedy. These human experiences make the actual weight of the event more tangible. For example, several of the firefighters captured at Ground Zero became heroes, their photographs representing bravery in the face of insurmountable odds. The images of individuals fleeing the collapsing skyscrapers, coated in ash, and citizens watching in despair from the streets serve as a constant reminder of the frailty and fragility of existence. However, each shot contains a silent tribute to the innumerable unsung heroes who appeared in those tumultuous times.

Photographers on the ground that day faced unprecedented hurdles. Capturing these moments required enormous courage and mental focus as the attack unfolded in real time. Photographers such as James Nachtwey, noted for his work in conflict zones, photographed the spreading mayhem while balancing the necessity to capture history with the ethical implications of documenting such severe human misery. These photographers, often at considerable personal risk, produced photos that were more than just snapshots, but historical records. Their work proved critical to the global understanding of the event, influencing how the world perceived and digested it. Each photograph presented a story that went beyond the confines of New York City, conveying the seriousness of the moment to all viewers, regardless of where they were.

The photos from that day had a global impact, shaping not just America’s but also the international community’s reaction to the catastrophe. As the photographs spread through traditional and digital media, they elicited a sense of shared empathy beyond national lines. The scenes of destruction, heroism, and sadness brought people together in their grief, making the attacks a worldwide experience rather than just an American one. The images of smoke pouring from the towers, people fleeing the streets, and first responders running towards the rubble were instantly recognised around the world. In the aftermath, these photos came to represent both fragility and resilience. They enabled the global public to engage with the event in ways that would have been unthinkable without such visual documentation.

Photographers faced ethical challenges when recording such a sensitive and tragic occasion. Editors and photographers were forced to make difficult decisions about what to show and what to keep. Balancing the public’s right to see history with the obligation to protect the victims’ dignity was an ongoing struggle. Photos like “The Falling Man,” while striking, provoked controversy about whether such intimate depictions of death should be shared with the public. This ethical tightrope walk serves as a reminder of photography’s difficult role in capturing history. It portrays reality in its most raw form while also navigating the emotional and moral ramifications of depicting suffering, particularly on such a large scale.

Following the disaster, photography continued to play an important role—not only in recalling the attacks, but also in chronicling the recovery process. Images of New York’s resiliency, ranging from the Tribute in Light to the first steps towards rebuilding the World Trade Centre, were strong emblems of hope and healing. Photos of survivors, first responders, and relatives visiting memorial locations served as reminders that life went on and that, albeit slow, healing was possible. These images have become as much a part of the event’s legacy as photographs of the attacks themselves. They represent not only loss but also rejuvenation, emphasising the resilience of the human spirit.

The significance of these classic photos continues to influence how we recall that awful day. They have been kept in museums, memorials, and history books, so that the stories they tell will never be forgotten. They serve not just as historical records, but also as lessons for the future, reminding us of the strength that comes from solidarity, even in the face of tremendous odds. As we look on the photos from that day, we are reminded of how powerful photography is in changing our view of history. These photographs continue to elicit strong emotions and will forever represent the fragility and resilience of the human soul.

England's Golden Age of Discovery and Drama Under the Tudor Queen

When Elizabeth I ascended to the throne in 1558, England was in turmoil, having recovered from years of religious conflict and economic instability. However, under her leadership, the country underwent an unparalleled transition. Elizabeth’s political savvy and cautious diplomacy ushered in a period of prosperity and peace, laying the groundwork for what many historians refer to as England’s “Golden Age.” Her reign became a symbol of national pride and solidarity, with the Queen representing grace, wisdom, and resilience.

One of Elizabeth’s most significant accomplishments was the establishment of the Church of England, which established Protestantism as the country’s official religion. By doing so, she avoided the religious wars that afflicted much of Europe. Her stance was strong but pragmatic, allowing for some religious tolerance while keeping the kingdom intact. With religious conflicts at bay, Elizabeth’s reign centred on promoting the arts, exploration, and commerce—elements that would come to define this thriving period.

During the Theatrical Renaissance in England, a new crop of dramatists rose to prominence and left a lasting impact on literature. The names William Shakespeare, Christopher Marlowe, and Ben Jonson were synonymous with the richness of English drama. Plays were no longer just for entertainment; they reflected society’s complicated ideals, from kings’ successes and difficulties to the daily lives of regular inhabitants. The rise of the Globe Theatre provided a forum for people from all walks of life to come together. Whether aristocratic or lowly, they were drawn by stories about love, betrayal, and ambition. Shakespeare, in particular, captured the human experience with a universality that transcended class, and his works remain relevant today. The arts flourished not only on the theatre, but also in music, poetry, and visual art, transforming England into a cultural superpower.

As English innovation flourished on land, the country’s explorers blazed new trails across the sea. The Queen’s encouragement for marine endeavours helped England become a powerful naval power. Sir Francis Drake’s circuit of the globe and Sir Walter Raleigh’s excursions to the New World were more than just heroic exploits; they represented England’s growing ambition. The destruction of the Spanish Armada in 1588 cemented England’s position as a maritime powerhouse, ensuring the country’s future in global trade and colonisation. These travels brought both wealth and knowledge. New territories opened up new economic opportunities, and Elizabeth’s government was keen to capitalise on the Americas’ riches. The period laid the groundwork for what would become the British Empire, ushering in a centuries-long legacy of exploration and colonialism.

While the magnificence of Elizabeth’s court is well documented, the daily lives of ordinary Englishmen and women reveal a different aspect of the story. England was a nation of sharp contrasts. The nobility lived in luxury, wearing exquisite silk, velvet, and lace garments, while the peasants laboured in the fields, their lives regulated by the agricultural calendar. The Enclosure Movement, which saw common lands converted into private property, displaced many rural people, driving them to towns and cities in search of work. Everyone, from the queen to the lowest labourer, knew where they stood in the social structure. Nonetheless, even within these rigorous institutions, there were moments of joy and celebration. Public holidays, fairs, and festivals provided small respites from the monotony of daily life, with music, dance, and dramatic performances showcasing the cultural richness that marked the age.

Clothing in the late 16th century was more than just a need; it was a symbol of prestige, riches, and power. Elizabeth herself became a fashion star, with lavish garments embellished with pearls, diamonds, and delicate embroidery. The Queen’s clothing was so important that sumptuary regulations were developed to govern what people of various social groups may wear. Purple was a royal colour, and particular textiles were only available to the upper classes. Dressing in the finest apparel was crucial to the nobility’s standing. Their extravagant dress reflected the richness of the Elizabethan court, with fashion functioning as a visual depiction of social hierarchy. At the same time, it was a time when the lower classes discovered ways to emulate the styles of their superiors, albeit in more humble ways.

While fashion may have controlled the court, intellectual curiosity thrived in other groups. Figures such as Sir Francis Bacon, a philosopher and statesman, began to challenge the limits of human knowledge. Bacon’s encouragement for empirical research created the framework for the Scientific Revolution, which occurred in the seventeenth century. The period saw a surge in interest in the natural world, the stars, and even mystical techniques such as alchemy and astrology.

Although science was still in its infancy, there was a desire for discovery that mirrored the country’s growth over the oceans. The era’s intellectual fervour fostered the growth of new ideas, which influenced the fields of philosophy, medicine, and astronomy. In many respects, Elizabethan England foreshadowed the Age of Enlightenment that would soon sweep across Europe.

Religion has long divided England, but Elizabeth’s reign brought some closure to the issue. Her father, Henry VIII, had left the Catholic Church, but it was Elizabeth who established Protestantism’s solid position as the national faith. The Church of England emerged as a unifying factor, and the Queen’s moderate policies helped to prevent the religious wars that were ripping Europe apart.

However, maintaining this equilibrium proved difficult. Catholics in England remained a possible threat, and the Pope’s excommunication of Elizabeth in 1570 exacerbated the situation. Nonetheless, Elizabeth managed to retain the peace by cautious diplomacy and a combination of firmness and tolerance, allowing her subjects to prosper in an environment of relative religious harmony.

By the time Elizabeth died in 1603, the foundations of a strong and culturally wealthy England had been laid. Her reign made an indelible mark on culture and identity, as well as on political stability and economic progress. The age of Shakespeare, the destruction of the Spanish Armada, and the emergence of England’s imperial ambitions all contributed to this watershed point in history. Elizabeth’s reign paved the way for the future, influencing the direction of British history for generations. This transformational age laid the groundwork for the British Empire, the development of English literature and drama, and the birth of a scientific worldview. As England entered the seventeenth century, it carried with it the spirit of the Golden Age, eternally defined by the reign of its indomitable Queen.

Celebrating The Spirit of Live Long and Prosper

Few events in science fiction history have had such a deep impact as Star Trek. The trailblazing series premiered on September 8, 1966, with a desire to boldly go where no one has gone before. Star Trek, created by Gene Roddenberry, was more than just a television show; it was a cultural touchstone that revolutionised the genre and inspired millions of fans worldwide. Star Trek’s origins are strongly steeped in Roddenberry’s vision of a utopian future in which humanity has overcome its past conflicts to embrace exploration and togetherness. Roddenberry, a former police officer and aspiring writer, drew on his experiences and a positive attitude for the future to create a series that challenged present societal standards and expanded the bounds of storytelling. The show’s setting on the starship USS Enterprise provides a platform for examining philosophical, sociological, and ethical issues through the lens of galactic adventure.

Spock, the half-human, half-Vulcan science officer, is central to this groundbreaking series and has an impact that transcends beyond the show’s borders. Spock, portrayed by the great Leonard Nimoy, became one of television’s most distinctive and popular characters. With his unique Vulcan ears and austere demeanour, he embodies rationality and reason, providing a contrast to the passionate and frequently chaotic aspect of human life. Spock’s character was created to examine the conflict between emotion and rationality, which reflects larger questions of identity and belonging. His battle with his dual lineage, straddling the line between his Vulcan upbringing and human emotions, struck a chord with viewers and provided a profound reflection on the nature of self and society. Nimoy’s portrayal of Spock, highlighted by a nuanced acting and thorough grasp of the character, elevated him from a mere fictitious construct to a symbol of intellectual inquiry and moral integrity.

Spock’s legacy includes the Vulcan Salute, which has become an enduring icon of Star Trek’s cultural significance. The salute, a hand gesture in which the fingers form a V shape, was inspired by Nimoy’s Jewish history. During an episode of Star Trek called “Amok Time,” Nimoy introduced the salute as part of the Vulcan ceremonial welcome. The gesture is accompanied by the words “Live long and prosper,” which represents the Vulcan ideal of peace and well-being. The Vulcan Salute can be traced back to Nimoy’s boyhood experiences at his synagogue, where he saw a priest do a similar gesture during religious events. This relationship filled the greeting with authenticity and cultural importance, adding dimension to the series’ depiction of Vulcan civilisation. The greeting has already transcended its fictional roots, becoming a well-known symbol of kindness and a tribute to Star Trek’s lasting impact.

The Vulcan Salute, like Spock, is more than just a cultural artefact; it exemplifies the virtues of cooperation, respect, and intellectual endeavour that Star Trek promoted. Its success reflects the series’ deep impact on its viewers, which fostered a sense of community and shared beliefs among them. As we commemorate Star Trek Day, it is appropriate to reflect on the series’ and characters’ enormous impact. Star Trek’s examination of complicated subjects, as well as its vision of a hopeful future, continue to inspire and connect with fans. The legacy of Spock and the Vulcan Salute exemplifies storytelling’s ability to cross cultural differences and awaken imaginations.

In a world that frequently appears broken and divided, Star Trek’s precepts are as pertinent as ever. The series, with its imaginative storytelling and famous characters, has created a framework for understanding and appreciating our common humanity. The Vulcan Salute, with its simple yet meaningful gesture, symbolises Star Trek’s undying spirit of exploration and the pursuit of knowledge. As we celebrate this important day, let us remember Star Trek’s history and devotion to exploring the unknown, accepting diversity, and creating a more educated and connected world. The journey of Star Trek is far from ended, and its legacy will definitely impact and inspire future generations of visionaries and explorers.