The Compact Camera That Changed The World

The 35mm film format transformed the field of photography by making it more accessible, portable, and innovative. This achievement dates back to the early twentieth century, and it owes much of its success to Oskar Barnack, a visionary engineer. His creativity, along with a growing desire for lightweight cameras, ushered in a new era of photography that would have a long-term impact on both professional and amateur photographers.

Prior to the introduction of 35mm film, photography was a time-consuming process. Early cameras were huge and frequently required tripods, and the film they utilised was cumbersome. Cameras were often built with glass plates or medium-format roll film, which made them bulky and difficult to transport. However, things began to change in the 1920s, when Oskar Barnack, an engineer at the Leitz firm (later known as Leica), pioneered the development of a more compact photographic equipment.

Barnack’s breakthrough idea stemmed from his unhappiness with the photographic technology available at the time. As an ardent photographer, Barnack was frequently irritated by the limits of large-format cameras. They were not only difficult to transport, but they also required long exposure periods, which made it impossible to catch moving scenes. His objective was clear: he wanted to design a camera that was portable, adaptable, and capable of shooting high-quality photographs with ease. This notion resulted in the creation of the 35mm format, a watershed moment in photography history.

Oskar Barnack’s adventure started in the early 1900s. Born in Germany in 1879, he began his career as a precision mechanic before joining Ernst Leitz Optische Werke in 1911. Barnack was tasked at Leitz with tackling a critical problem: developing a portable motion picture camera for use in the field. In 1892, Thomas Edison and William Dickson established 35mm film stock as the standard in cinema. However, Barnack saw possibilities in using the same film for still photography, which was a dramatic departure from existing camera technology.

He developed the Ur-Leica (short for “Leitz Camera”) prototype in 1913. This small camera was revolutionary since it used 35mm film, which is generally reserved for cinematic pictures. What set it apart from earlier cameras was its capacity to expose a small, exact area of the film, allowing several photos to be captured on a single roll. This led to the invention of taking numerous frames in succession, which is an important aspect in making photography both accessible and efficient.

While Barnack’s Ur-Leica prototype was completed in 1913, the outbreak of World War I postponed its further development and commercialisation. However, the framework had been established. Barnack’s innovation stemmed from his decision to employ a film format that was widely available but underutilised for still photos. The 35mm film format provided various advantages, including portability, rapid exposure, and the ability to take more photographs each roll. These characteristics were highly valued for both experts and enthusiasts looking to push the limits of their craft.

In 1925, the Leitz business officially debuted the Leica I, the first commercial 35mm camera. Its small size, combined with high-quality lenses and portability, made it an instant hit. The Leica I revolutionised the photographic profession by changing the way photographers approached their job. Instead of relying on bulky equipment and limited mobility, they could now transport a compact camera that provided tremendous creative freedom.

The 35mm film format’s adaptability was essential to its appeal. Photographers might use smaller film stock to obtain 36 exposures on a single roll. This was a significant advance over larger formats, which typically allowed only a few images before requiring film changes. The 35mm format also offered technological advantages: because the film was compact, lenses could be constructed to provide sharper resolution and greater detail, allowing photographers to produce high-quality pictures.

For photojournalists, the 35mm format was a boon. Its lightweight and small design allowed photographers to operate in situations where speed and discretion were critical. Henri Cartier-Bresson, a famed photographer and pioneer of street photography, famously employed Leica cameras to capture candid moments that would have been impossible with larger cameras in the past.

Similarly, documentary photographers preferred the 35mm format for fieldwork. Robert Capa, one of the most well-known combat photographers of the twentieth century, used his Leica to take striking, dynamic photos on the front lines of conflict. His iconic photos from the Spanish Civil War and the D-Day landings during World War II were captured with 35mm cameras, emphasising the format’s importance in documenting historical events.

While 35mm film was originally created for motion movies, it acquired popularity in still photography due to the success of Leica cameras. In the 1930s and 1940s, other camera manufacturers began to use the 35mm format, resulting in a surge in the popularity of tiny cameras. Companies including Contax, Nikon, and Canon began making models based on Barnack’s original Leica.

In addition to its influence on professional photography, the 35mm format grew popular with hobbyists and amateurs. By the mid-twentieth century, cheap 35mm cameras had enabled people from many areas of life to pursue photography as an art form. The introduction of colour film in the 1930s, followed by Kodak’s popular Kodachrome in 1935, greatly increased the possibilities of 35mm photography, making it the preferred format for both black-and-white and colour photography.

The format’s adaptability also extended to cinema. Directors and cinematographers discovered that 35mm film was an appropriate medium for producing high-quality motion pictures. From Hollywood blockbusters to smaller films, 35mm became the industry standard, requiring exact image quality and dependable film stock.

Today, the 35mm format has a unique role in both photographic history and modern practice. Although digital photography has mostly overtaken film in the twenty-first century, 35mm film is still a popular medium among photographers who value the particular look it provides. Film’s grain, colour reproduction, and dynamic range are difficult to mimic digitally, hence many photographers continue to shoot with film even in the digital age.

Furthermore, the heritage of Oskar Barnack and his pioneering work with 35mm film lives on through the continuous use of Leica cameras. Leica remains identified with precision engineering, high-quality optics, and timeless design, and its cameras are still covered by photographers who appreciate workmanship and heritage.

The 35mm film format transformed photography by making it more accessible, portable, and innovative. Oskar Barnack’s goal of developing a tiny camera that could use 35mm motion picture film changed the photographic world forever. From the launch of the Ur-Leica to the widespread use of the format by pros and hobbyists alike, 35mm film has influenced how we capture the world around us. Its legacy, in both still photography and cinema, continues to demonstrate the power of invention, inventiveness, and the pursuit of excellence in capturing life’s ephemeral moments.

Raise a Stein: Oktoberfest is Here!

Every October, the world raises a glass in honour of a centuries-old tradition that began in the heart of Bavaria: Oktoberfest. While the name conjures up pictures of foaming steins and busy beer halls, the history of Oktoberfest is far more interesting than a mere beer celebration. This legendary event, celebrated yearly in Munich and duplicated around the world, is based on a royal wedding, a time-honoured cultural tradition, and a global need for community and mirth.

The first Oktoberfest in German, took place on 12 October 1810. The occasion was the marriage of Crown Prince Ludwig of Bavaria (later King Ludwig I) and Princess Therese of Saxe-Hildburghausen. To commemorate this blissful coupling, the royal family asked Munich residents to join in the celebrations on the fields outside the city gates. These grounds, which became known as Theresienwiese (“Theresa’s Meadow”) in honour of the bride, continue to constitute the focal point of the event today. The first Oktoberfest featured a horse race, which pleased the citizens and established the tone for future events. The event was such a success that it became an annual tradition, eventually growing into the world-famous festival we know today.

While beer has become synonymous with Oktoberfest, it was not always the main attraction. In its early years, the festival was largely an agricultural display intended to promote Bavarian agriculture. For decades, Oktoberfest was a celebration of area produce, cattle, and rural crafts. Farmers and breeders from all across Bavaria would bring their best animals and produce, transforming the event into a large-scale agricultural show honouring the region’s rural heritage. It wasn’t until the late nineteenth century that beer took centre stage. Breweries began erecting big beer tents to serve thirsty festivalgoers, and by the 1890s, these tents had expanded into massive constructions capable of accommodating thousands of people. With beer at the centre of the celebration, Oktoberfest evolved into the iconic event that now attracts millions of people from all over the world.

The beer is crucial to Oktoberfest, and it’s not just any beer. The festival highlights the Märzen variety, a typical Bavarian beer produced especially for the occasion. Märzen, with its amber colour, full-bodied flavour, and higher alcohol concentration, was traditionally produced in March and held in cold cellars all summer. By October, the beer was wonderfully matured and ready to drink. Only six breweries are licensed to serve beer at Oktoberfest, and they are all situated in Munich. For more than a century, these breweries—Augustiner, Hacker-Pschorr, Hofbräu, Löwenbräu, Paulaner, and Spaten—have been central to the festival’s character. Their beer, served in enormous one-litre Maß steins, is noted for its distinct, rich flavour, which embodies Bavarian workmanship and traditions.

Today, Oktoberfest has expanded well beyond its Bavarian origins. Every year, almost six million people from all over the world gather in Munich for the 16- to 18-day event, making it the world’s largest folk festival. But, beyond the beer tents, Oktoberfest is a multidimensional event with a variety of activities celebrating Bavarian culture.

- Parades and Traditions: The festival kicks off with a magnificent parade through Munich’s streets, showcasing traditional Bavarian costumes, brass bands and horse-drawn beer waggons. The mayor of Munich taps the first keg in a ceremonial opening, shouting, “O’zapft is!” (“It’s tapped!”) to herald the start of the celebration. There is also a traditional riflemen’s march, which highlights Bavaria’s historic military and cultural legacy.

- Cultural Shows: Aside from the beer, Oktoberfest is a festival of Bavarian art, music, and dancing. Every day, authentic Bavarian folk music fills the air, played by ensembles dressed in lederhosen and dirndls. In the afternoons, guests can see performances of **Schuhplattler**, an explosive Bavarian dance involving rhythmic stomping and slapping of the thighs and shoes.

- Carnival Rides and Games: In keeping with the festival’s roots as a public celebration, Oktoberfest also features a large funfair. Carnival rides, roller coasters and games offer enjoyment to individuals of all ages. The historic Flea Circus, a modest yet unique institution, has been entertaining guests for almost a century.

- Delicious Bavarian Food: No Oktoberfest is complete without the accompanying Bavarian specialities. From gigantic pretzels and grilled sausages to roasted chicken and hog knuckles, the cuisine at Oktoberfest is as important as the beer. The festival menu include traditional Bavarian foods such as Weißwurst (white sausage) and Schweinshaxe (roasted pork knuckle).

- Family-Friendly Days: While Oktoberfest is primarily focused on beer, it has also evolved into a family-friendly event. Special “Family Days” feature discounted rides, food, and attractions, making the event suitable for people of all ages. These days highlight Oktoberfest’s community-oriented atmosphere, with something for everyone.

While Munich’s Oktoberfest remains the crown gem, it has spawned similar events around the world. Cities such as Kitchener-Waterloo in Canada, Cincinnati in the United States, and Blumena in Brazil hold their own large-scale Oktoberfests, tailoring the Bavarian custom to their respective cultures. In these places, revellers congregate in beer halls, donning traditional Bavarian costumes and toasting with steins of beer, resulting in a shared global experience. The core of Oktoberfest—community, festivity, and a strong love for tradition—is felt across boundaries. Whether in Munich’s large beer tents or smaller gatherings in cities around the world, the festival reflects a spirit of joy and celebration that brings people together.

It is more than just a beer festival; it’s also a historical, cultural, and traditional event. Oktoberfest, which began as a royal wedding celebration and has now grown to become a global phenomenon, exemplifies the continuing appeal of Bavarian hospitality and workmanship. The festival evolves each year, but its core stays the same: a joyful celebration of life, community, and Bavaria’s rich traditions.

So, as the fresh October air fills the streets and the sound of clinking steins echoes around the world, take a time to raise your glass. Whether you’re in Munich or halfway around the world, the spirit of Oktoberfest lives on, encouraging us all to appreciate the joy of good company and shared customs. Prost!

Fall of The Qing Rise of The Republic

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, China stood at a crossroads. After centuries of dynastic rule by the Qing Dynasty, foreign intervention, and internal strife, the country was on the verge of a seismic shift. The establishment of the Republic of China in 1912 was a watershed moment in world history, signalling the end of over two millennia of imperial authority. This transformation was spearheaded by revolutionary thinkers, political reformers, and nationalist leaders who aimed to modernise China and restore sovereignty. The Republic’s origins are inextricably linked to the lives and achievements of its founders, including Sun Yat-sen, who imagined a new China free of the remnants of the past.

To understand the rise of the Republic of China, one must first examine the fall of the Qing Dynasty. The Qing dynasty, which ruled China for nearly three centuries, was established in 1644. However, by the mid-nineteenth century, the Qing faced severe external and internal obstacles. The dynasty had been badly weakened by the Opium Wars, which were fought with Britain over the opium trade, resulting in a series of unequal treaties that awarded Western powers enormous economic and territorial control of China.

Internal corruption and incompetence plagued the Qing administration, and natural calamities and famines exacerbated the empire’s instability. Perhaps the most damaging event was the Taiping Rebellion (1850-1864), a huge civil war headed by Hong Xiuquan, a religious leader who claimed to be Jesus Christ’s younger brother. The uprising killed an estimated 20-30 million people, depleting the Qing’s resources and authority. Following the uprising, the Self-Strengthening Movement, which sought to modernise China’s military and industrial capabilities, was too little, too late.

By the turn of the twentieth century, nationalist sentiment was on the increase. Intellectuals, scholars, and reformers began to doubt the legitimacy of imperial rule, calling for modernisation based on Western political values. The growth of Western education, the impact of democratic values, and the humiliation of the Boxer Rebellion (1899–1901) exacerbated the Qing’s problems.

Among the several figures driving the revolution, Sun Yat-sen is the most influential. Sun, often referred to as the “Father of the Nation,” was born in Guangdong Province in 1866 and spent much of his early life studying medicine in Hong Kong. However, his attention quickly switched from medicine to politics, especially after observing the inequities and inefficiencies of Qing governance. Sun grew convinced that China needed to be reformed as a modern republic founded on democratic principles.

Sun established the Revive China Society in 1894, a secret revolutionary organisation dedicated to overthrowing the Qing Dynasty. His vision was captured in the “Three Principles of the People”: nationalism, democracy, and people’s livelihood. Nationalism sought to exclude foreign influence and restore Chinese sovereignty, democracy envisioned a government elected by the people, and people’s livelihoods prioritised social welfare and economic modernisation. These concepts will subsequently serve as the cornerstone of the Republic of China.

Following multiple failed revolutions, Sun realised that overthrowing the Qing required a larger coalition of revolutionaries. In 1905, he contributed to the formation of the Tongmenghui (United League), a coalition of anti-Qing factions. Sun travelled extensively over the following several years, seeking financial and political support for his cause from Chinese groups and governments abroad.

The Wuchang Uprising of 1911 sparked the Xinhai Revolution. On 10 October 1911, a group of dissatisfied soldiers in Wuchang, Hubei Province, began an insurrection against Qing troops. This seemingly localised insurrection spread fast throughout the country, with province after province declaring independence from the Qing authorities. By the end of 1911, the Qing Dynasty was in disarray, unable to muster the military or political might to put down the uprising.

Sun Yat-sen was declared interim president of the newly created Republic of China on 1 January 1912, in Nanjing. This signalled the end of more than two millennia of imperial control and the start of a new era. However, Sun’s presidency was short-lived. Sun, lacking military power, was compelled to hand up the presidency to Yuan Shikai, a former Qing officer, in order to achieve the abdication of the Qing Emperor, Puyi, in February 1912.

Although the Qing Dynasty had fallen, the Republic’s early years were anything but stable. Sun Yat-sen’s concept of a democratic republic contrasted with Yuan Shikai’s authoritarian goals. Yuan, who had won the presidency with military support, moved quickly to solidify control. By 1915, he had declared himself emperor and hoped to restore imperial sovereignty under his leadership. This move sparked considerable resentment and resulted in other rebellions, leading Yuan to abdicate the next year.

Yuan Shikai’s death in 1916 ushered China into the Warlord Era, a period of governmental disintegration that lasted until 1928. Various regional military leaders, sometimes known as warlords, dominated different regions of the country, undermining the Republic of China’s central authority. Despite the instability, Sun Yat-sen worked to unify China using the ideals of his revolutionary vision.

Sun Yat-sen created the Kuomintang (KMT), often known as the Nationalist Party of China, in 1919 to succeed the Tongmenghui. The KMT sought to unify China and follow Sun’s Three People’s Principles. Sun pursued partnerships with numerous political groupings during the following several years, as well as with the Soviet Union, which gave the KMT with military and financial assistance. The Soviets also encouraged Sun to work with the newly created Chinese Communist Party (CCP), resulting in a temporary collaboration between the two parties.

Sun Yat-sen died of liver cancer in 1925, leaving the nationalist movement without a leader. His successor, Chiang Kai-shek, would carry on Sun’s legacy, commanding the KMT in the Northern Expedition (1926-1928), a military campaign aimed at conquering the warlords and reuniting China. By 1928, Chiang had successfully consolidated authority over much of China, creating the Nationalist administration in Nanjing. This marked the start of the so-called Nanjing Decade (1928-1937), a period of relative stability and modernisation under KMT control.

The Republic of China’s early history was characterised by both triumph and upheaval. Sun Yat-sen’s ideal of a modern, democratic China was never fully realised during his lifetime, but his ideas remained influential in Chinese politics for decades. The Republic faced numerous problems, including internal power struggles and foreign invasions, the most notable of which was the Japanese invasion in the 1930s, but its establishment was a watershed moment in Chinese history.

Sun Yat-sen’s principles of nationalism, democracy, and the people’s livelihood left an indelible mark, even as China’s political environment evolved radically in the years that followed. Today, the Republic of China remains on the island of Taiwan, where it relocated following the Chinese Civil War, which saw the creation of the People’s Republic of China on the mainland under Communist government.

The establishment of the Republic of China in 1912 was more than just a shift in political leadership; it was the result of years of intellectual discussion, revolutionary zeal, and a deep longing for national rejuvenation. While the Republic experienced significant challenges in its early years, its establishment signalled the start of modern Chinese history, a period of dramatic development that continues to determine the country’s identity today.

The Dark Chapter of Indonesian History

Every year on 1 October, Indonesia marks Hari Kesaktian Pancasila (Pancasila Sanctity Day), a solemn reminder of the country’s resilience in the face of dividing forces. It represents the triumph of Indonesia’s basic values, as codified in Pancasila, over a period of deep national turmoil. This day commemorates not just the preservation of Pancasila, but also the long-lasting unity of a country whose history has been marked by political turmoil.

The events leading up to the annual remembrance of Hari Kesaktian Pancasila are inextricably linked to the events of 30 September 1965, a tragic day in Indonesian history. A covert movement known as Gerakan 30 September (G30S) launched a deadly coup attempt. A group of the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI) started the operation with the goal of overthrowing the government and establishing a communist rule. Key Indonesian military commanders were targeted in a painstakingly planned operation, with seven high-ranking army officers abducted and brutally slain. This act of violence caused a nationwide shock, known as the G30S incident.

The G30S movement’s motivations were complicated, stemming from political and ideological tensions between the military and PKI. Throughout the early 1960s, Indonesia was in ideological turmoil, with President Sukarno striving to strike a balance between communism, nationalism, and religion. The coup attempt was a tipping point that threatened to plunge Indonesia into civil war.

The events of 30th September triggered a rapid and resolute national response. On the morning of 1 October 1965, the military, led by Major General Suharto, suppressed the rebellion and regained control of Jakarta. Suharto’s quick steps were vital to restoring order and neutralising the PKI threat. The defeat of the coup d’état prepared the door for Pancasila Sanctity Day, a symbolic day commemorating the survival and sanctity of the Pancasila doctrine.

Pancasila, Indonesia’s founding ideological theory, is based on five principles: belief in one God, a just and civilised mankind, Indonesian unity, democracy guided by the wisdom of representatives, and social justice for all Indonesians. These ideals act as a unifying factor in a multicultural and pluralistic country. Despite an attempted overthrow, Pancasila emerged stronger, reaffirming its status as the nation’s guiding light.

Following the coup, Indonesia experienced significant political and social instability. In the months that followed, there was a statewide purge of alleged PKI members and sympathisers, ushering in one of Indonesia’s darkest periods. Hundreds of thousands of people were killed during the military-led campaign to apprehend communist organisations and suspected affiliates. This phase of anti-communist sentiment profoundly transformed the political landscape in Indonesia, cementing Major General Suharto’s position as the country’s de facto leader.

In 1967, Suharto officially acquired the presidency, ushering in the New Order era. His administration emphasised Pancasila as a foundation of national identity, incorporating its ideas into educational curricula, administrative programs, and the fabric of Indonesian society. Hari Kesaktian Pancasila has become an important annual festival, a day to reflect on the country’s resilience and principles.

Hari Kesaktian Pancasila is more than just a memorial to a failed coup; it symbolises Indonesia’s everlasting dedication to its national ideology. On this day, the nation reflects on the historical lessons learnt from the events of 1965 and renews its commitment to Pancasila as the foundation of governance and national unity. Ceremonies are held across the country, with a significant state event taking place at the Pancasila Sakti Monument in Lubang Buaya, Jakarta, where the assassinated generals are interred. The Indonesian President traditionally leads this solemn ceremony, which includes military processions and prayers for the martyrs who have died. Schools and institutions engage in festivities, ensuring that future generations understand the significance of this day in preserving national unity.

The observance emphasises the importance of pluralism in a country as diverse as Indonesia, with its numerous races, faiths, and languages. Pancasila serves as a bridge between these disparities, encouraging a feeling of shared purpose. Indonesians commemorate the sanctity of Pancasila by honouring the key ideas that have kept the country united in the face of external and internal forces.

Today, the Pancasila values remain important to Indonesian politics and society, even as the country’s issues grow. In today’s political scene, when extremism, corruption, and global economic upheavals abound, Pancasila’s demand for unity and social justice is more important than ever. However, there is ongoing dispute regarding how to interpret and execute its values. Some say that certain members of the political class have utilised Pancasila as a weapon to consolidate power rather than as an ideology to benefit the people. In recent years, there have been efforts to strengthen Pancasila education, particularly among young people. The Indonesian government continues to promote its values as critical to sustaining national stability and progress, especially in the face of globalisation and internal polarisation.

At its essence, Hari Kesaktian Pancasila is a day for introspection. It serves as a reminder of Indonesia’s strength, which is its capacity to retain togetherness in the face of variety. The durability of Pancasila, as exemplified by the events of 1965, demonstrates the country’s commitment to coexistence and peace. As the country progresses, the lessons learnt from this historical period remain critical. Just as the Indonesian people remained steady in protecting their ideological underpinning during a crisis, they are now expected to sustain the same values—democracy, fairness, and unity—in the face of new obstacles.

Hari Kesaktian Pancasila is both a monument to a near-collapse and a celebration of national principles. It is a sorrowful but hopeful reminder that Indonesia’s greatest strength is its capacity to remain unified in diversity while adhering to the eternal Pancasila principles.

Leave Only Footprints, Take Only Memories

World Tourism Day, observed annually on September 27, serves as a reminder of tourism’s tremendous impact on our global economy, cultures, and environment. It is a day set aside to recognise the role tourism plays in promoting mutual understanding, economic prosperity, and environmental preservation. However, as the twenty-first century progresses, the relationship between tourism and sustainability has grown in importance. Today, it is critical to consider how sustainable travel may impact the future of tourism, ensuring that the wonders of our globe are maintained for future generations.

Tourism as we know it now is a relatively new phenomenon, fuelled by the Industrial Revolution of the nineteenth century. During this time, technological breakthroughs like steamships and railroads made long-distance travel more accessible to the general public. However, the concept of tourism goes far further back—ancient Greeks and Romans travelled for pleasure, visiting monuments, spas, and temples, laying the groundwork for what would become a lucrative industry.

By the mid-twentieth century, tourism had grown into a global industry, with air travel transforming international exploration. The expansion of tourism offered enormous benefits: increased chances for cultural interaction, a thriving hospitality industry, and enhanced economic development, particularly in nations with natural or historical sites. However, with increased tourism came new issues, especially environmental deterioration, overtourism, and the exploitation of indigenous traditions.

This is where the discourse about sustainable tourism started. Over the last few decades, there has been a growing push to ensure that tourism not only benefits travellers but also protects and preserves the areas they visit. Sustainable tourism is defined as tourism that serves the requirements of both tourists and host communities while safeguarding and expanding future prospects. In other words, it seeks to reduce the negative effects of travel while increasing the advantages. This entails focussing on three major pillars: environmental sustainability, sociocultural preservation, and economic viability.

- Environmental Sustainability: This refers to methods that reduce the carbon impact of travel, protect wildlife, and preserve natural landscapes. Popular tourist attractions, including the Great Barrier Reef, Machu Picchu, and Venice, have all suffered environmental degradation as a result of overtourism, pollution, and unsustainable practices. Sustainable tourism promotes activities such as environmentally friendly transportation, waste reduction, and conservation efforts.

- Socio-Cultural Preservation: Tourism can have a positive and negative impact on local populations. While it provides much-needed economic opportunities, it may also result in cultural commodification and the destruction of local customs. Sustainable tourism emphasises the necessity of respecting local cultures, assisting indigenous communities, and fostering authentic, responsible tourists.

- Economic viability: Sustainable tourism seeks to divide the economic advantages of travel fairly among stakeholders. This involves ensuring that the local community, rather than just major enterprises, reaps the benefits of tourism through projects like community-based tourism, in which local citizens directly benefit from tourist activities.

Tourism and sustainability are more than a trend; they are a requirement. As the climate issue intensifies, the tourism sector must evolve. The United Nations has long recognised this, including sustainable tourism among its Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Goal 12.7 specifically asks for the promotion of sustainable tourism that generates jobs while also promoting local culture and products.

Several countries have responded to the challenge, making sustainability a key component of their tourism strategy. Bhutan, for example, has developed a “high-value, low-impact” tourism strategy that limits the number of tourists allowed in the nation and charges a daily fee to fund conservation efforts and community development. Similarly, Costa Rica has established itself as a leader in eco-tourism, with approximately 30% of its territory classified as protected land. In Europe, efforts such as the Green Key program recognise hotels and other tourism-related enterprises that fulfil high environmental standards, encouraging eco-friendly practices throughout the industry.

Consider a traveler embarking on a trip through Peru. Instead of joining the crowds that visit Machu Picchu every day, which contributes to the degradation of the historic monument, they take a less-known route: the Salkantay Trek. This alternate route provides breathtaking vistas of the Andes while reducing pressure on Machu Picchu’s delicate ecosystem. By staying at locally owned accommodations along the journey, the traveler ensures that their money goes directly to the indigenous Quechua communities that live in these mountains.

Such stories are more than simply individual choices; they represent a bigger tourist movement. Travellers can affect the future of tourism by making informed, responsible decisions. This narrative is gaining popularity as individuals become more aware of the environmental and cultural effects of their activities. Furthermore, sustainable travel experiences provide more fulfilling and enriching journeys. Engaging with local cultures, learning about a place’s history and traditions, and making a good influence can make travel more rewarding for both the visitor and the people involved.

Technology has emerged as a significant actor in the quest for sustainable tourism. From carbon offset programs integrated into ticket bookings to apps that assist travellers in reducing waste, technology provides novel solutions for decreasing the environmental effect of travel. Smart tourism—an emerging idea that uses data to optimise tourism experiences—allows cities to better manage tourist flows and avoid congestion in popular places.

For example, Barcelona uses sensors to monitor crowd levels at famous monuments such as La Sagrada Familia, changing suggestions and visitor patterns in real time to avoid overcrowding in certain places. This type of technology ensures that tourism does not have a negative impact on local quality of life while yet allowing visitors to enjoy their experience.

As we look ahead, sustainable tourism is expected to play a critical part in the rehabilitation of the travel sector following the epidemic. The epidemic served as a clear reminder of how overtourism has harmed many areas, and the sector now has a rare opportunity to rebuild in a sustainable manner. Governments, businesses, and travellers must all work together to guarantee that tourism not only returns, but grows stronger, more inclusive, and sustainable. This could include marketing lesser-known sites, investing in sustainable infrastructure, and instilling a culture of environmental and cultural stewardship.

On this World Tourism Day, we are reminded that tourism is more than just visiting new places; it is also about honouring and protecting the environment. Sustainable tourism is not simply an option; it is required if we are to continue enjoying our planet’s beauty and diversity without creating irreversible damage.

As travellers, we have the ability to make decisions that are consistent with these principles, such as supporting eco-friendly hotels, limiting trash, and engaging with local communities ethically. As we commemorate this day, let us pledge to make travel a force for good, ensuring that future generations can appreciate the beauties of our planet as we do now.

Happy World Tourism Day! Let us travel mindfully, investigate carefully, and guard passionately.

The World's Most Knowledgeable Know-It-All

On September 27, we celebrate the birth of one of the most disruptive forces in the digital age: Google. Google was founded in 1998 by Larry Page and Sergey Brin while they were both PhD students at Stanford University. However, its ambition was far greater. What began as a research initiative to improve the accuracy of search results has grown into a multi-faceted technological behemoth that influences how we access information, interact, and do business.

Google’s origin was highlighted by the creation of the PageRank algorithm, a groundbreaking technique to categorising web sites based on their relevancy and the amount of links connecting to them. Unlike its competitors, which focused on keyword matching, PageRank provided a more comprehensive understanding of a page’s importance, resulting in more accurate search results. This breakthrough laid the groundwork for Google’s spectacular development, enabling it to outperform competitors like Yahoo! and AltaVista, which were dominant at the time.

It’s growth rate was nothing short of phenomenal. By the early 2000s, the business had expanded its capabilities, including Gmail in 2004 and Google Maps in 2005. Gmail revolutionised email with its large storage capacity and creative features such as conversation threading, while Google Maps transformed navigation with satellite images and real-time traffic reports. Google’s acquisition of YouTube in 2006 reinforced its dominance in internet video by offering a platform for anybody to share and find content globally.

Google launched the Android operating system in 2008, and it soon rose to prominence in the mobile market. Android’s open-source model empowers developers globally, resulting in a vast range of applications and devices that continue to improve the user experience today. This adaptability has enabled Google to remain at the forefront of technological innovation, assuring its continued relevance in an ever-changing digital landscape.

Despite its numerous triumphs, Google has faced hurdles. The corporation has been scrutinised for privacy concerns, notably over its data collection techniques. The Cambridge Analytica scandal in 2018 raised serious concerns about how user data was managed across platforms, sparking public outrage and governmental scrutiny. Google’s efforts to combine user privacy with advertising demands have frequently been criticised, illustrating the complexity of functioning as a global corporate behemoth.

Furthermore, the corporation has experienced difficulties in a variety of endeavours, including the debut of Google Glass in 2013. While the augmented reality device promised to revolutionise personal computing, it was eventually discontinued due to public concerns about privacy and usability. Such obstacles underscore the difficulties of developing new technologies, where user approval and market readiness are critical to the success of creative products.

Today, Google remains a technology industry stalwart, adapting to new challenges while always innovating. The rise of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning has spurred Google to improve its search engines and broaden its product portfolio. The advent of Google Assistant, as well as advances in natural language processing, demonstrate Google’s dedication to integrate AI into everyday life, making technology more intuitive and accessible. Furthermore, Google has made major investments in sustainability programs, aiming to run on renewable energy and lower its carbon footprint. This commitment not only addresses environmental concerns, but also appeals to a growing consumer base that values corporate responsibility.

Google has recently increased its attention on health technology, with programs like Google Health and partnerships aimed at using AI to improve patient care. This diversification highlights Google’s strategic agility, ensuring that it remains a key participant in various industries. As we celebrate Google’s birthday, it is critical to acknowledge the company’s tremendous influence on how we engage with information and technology. From a simple search engine to a worldwide behemoth, Google has continuously pushed the limits of what is possible. Its story demonstrates the power of invention, resilience, and a relentless pursuit of perfection.

Looking ahead, Google’s focus on research, development, and user-centric design will surely affect the next generation of technology. As we traverse the complexity of the digital age, Google will continue to shape how we connect, communicate, and grasp our surroundings. Reflecting on Google’s journey reminds us that innovation is a constant process with both successes and mistakes. Google’s capacity to adapt and reinvent itself in the face of adversity has cemented its position as a technological leader throughout history. As we commemorate another year since its creation, we recognise not only the firm but also the vision that drives it—a vision that will definitely evolve and inspire for years to come.

Afghanistan: A Monument to the Silk Road's Glory

In the ancient heart of Central Asia, where towering mountains embrace sprawling desert landscapes, lies Afghanistan—a land steeped in history and teeming with tales of trade and transformation. Picture a scene from centuries past: dusty caravanserais spring to life with the arrival of traders, their camels laden with precious silks, exotic spices, and ancient manuscripts. Here, amidst the rugged terrain and bustling marketplaces, Afghanistan stood as a vital crossroads on the Silk Road, where East met West in a grand tapestry of commerce and culture. This storied crossroads has witnessed the rise and fall of empires, the mingling of diverse peoples, and the flow of ideas and goods that shaped the course of history.

The Silk Road, an intricate web of commercial routes connecting China and the Mediterranean, served as a conduit for cultural and intellectual exchange as well as a means of transportation. Afghanistan, with its steep terrain and strategic location, served as an important link in this huge network. The region’s history is marked by the emergence and collapse of empires that exploited its potential as a commerce hub. The Greco-Bactrian Kingdom, the Kushan Empire, and subsequently the Sassanian and Islamic Caliphates recognised the importance of Afghanistan’s position. Balkh, sometimes known as the “Mother of Cities,” was a thriving cultural and commercial centre. Scholars, traders, and travellers from all backgrounds gathered here, trading not only products but also ideas and innovations.

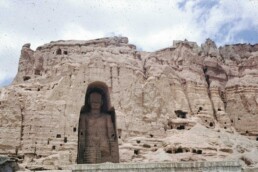

During the Kushan Empire (approximately 30-375 CE), Afghanistan saw one of its most amazing times on the Silk Road. The Kushans, descended from the Yuezhi tribes, founded a monarchy that spanned modern-day Afghanistan, northern India, and parts of Central Asia. Cities such as Bamiyan and Kabul thrived as melting pots of Greek, Persian, Indian, and Central Asian cultures during the Kushan era. The Kushans helped disseminate Buddhism from India to China via the Silk Road. The iconic Bamiyan Buddhas, huge statues carved into the cliffs of the Bamiyan Valley, are a witness to this cultural blending. Despite their sad destruction in 2001, these statues continue to represent Afghanistan’s rich historical heritage.

Samarkand, a prominent Silk Road stop in northern Afghanistan, was another important trading and cultural centre. While Samarkand is not in present-day Afghanistan, its historical impact on the region was significant. As merchants and academics travelled the Silk Road, they regularly passed through Afghanistan. The interchange of items including textiles, ceramics, and precious stones helped Afghan cities develop. This age also saw the introduction of new technology and ideas, including as advances in astronomy, mathematics, and medicine, which spread across the region via the Silk Road. This cross-cultural interaction fuelled the creation of a complex urban culture that distinguished many Afghan cities.

Afghanistan’s importance on the Silk Road changed dramatically during the 7th and 8th centuries as Islam spread. The Umayyad Caliphate’s expansion into Central Asia created new trade routes, further integrating Afghanistan into the Islamic world. The Abbasid Caliphate, which succeeded the Umayyads, inaugurated a golden period of cultural and scientific progress. Cities such as Herat and Ghazni have arisen as thriving centres of Islamic culture and learning. The scholarly work created in these cities left an indelible mark on the intellectual landscape of the time. The Persian polymath Avicenna, also known as Ibn Sina, was a major person during this period. Avicenna, who was born in the region, made significant contributions to medicine, philosophy, and natural sciences. His publications, particularly “The Canon of Medicine,” had a significant impact in both the Islamic world and mediaeval Europe, illustrating Afghanistan’s significance as a link between East and West.

The emergence of the Mongol Empire in the 13th century represented another watershed moment for Afghanistan. Genghis Khan’s conquests, followed by Timurid reign, changed Central Asia’s political environment. Despite the bloodshed and chaos, the Mongol era enabled additional cross-cultural interactions. The Timurids, noted for their encouragement of the arts and architecture, left an indelible mark on the region. Under Timur’s leadership, Herat rose to prominence as a centre of art, literature, and scholarship. The Timurid architectural style, known for its elaborate tile work and large monuments, continues to influence Afghan architecture today.

The fall of the Silk Road, caused in part by the growth of maritime trade routes and the Ottoman Empire’s dominance, was a fundamental shift in Afghanistan’s historical trajectory. The regional trade patterns shifted, but Afghanistan’s legacy remained a reminder of its former splendour. The relics of ancient cities, the echoes of former empires, and the persisting cultural interactions all contribute to a complicated and interesting story.

Today, Afghanistan’s heritage serves as both a reminder of its past and a beacon for future discovery. The old trade routes may have shrunk in their original shape, but the spirit of commerce and connection that distinguished the Silk Road persists. Afghanistan is a testimony to the Silk Road’s long-lasting legacy, reminding us of a period when faraway places were brought together by a shared desire of riches and knowledge. As we reflect on this illustrious past, we acquire a better understanding of how trade and culture interacted on this ancient route, changing the course of history and enriching the fabric of human civilisation.

The Silk Road’s influence on Afghanistan is a stark reminder of how interwoven our globe has always been. This old trade network’s legacy lives on in Afghanistan’s cultural and historical fabric, providing unique insights into the trade, culture, and civilisation forces that have defined our collective past. Exploring this rich past not only reveals the complexities of ancient commerce, but also provides a better understanding of how human interactions have crossed geographical and temporal boundaries.

Capturing Moments the Old-Fashioned Way

In an era dominated by digital technology, where quick gratification and the convenience of smartphone photography reign supreme, the resurrection of analogue cameras is both amazing and exciting. This comeback reflects a deeper cultural desire for authenticity, nostalgia, and the tactile involvement that analogue photography uniquely provides. As modern photographers and enthusiasts increasingly gravitate toward film cameras, it is vital to investigate the historical context, the reasons for this trend, and its implications for the future of photography.

The history of photography began in the early nineteenth century, when Louis Daguerre invented the daguerreotype in 1839. This pioneering approach paved the door for countless advances in photographic processes, including the invention of various types of film cameras throughout the twentieth century. In the 1920s, Leica and Nikon popularised the 35mm format, which became the norm for both professional and amateur photographers. This era saw the rise of great photographers such as Ansel Adams and Henri Cartier-Bresson, who used analogue cameras to record some of the most impactful photographs in photographic history.

However, the arrival of digital photography in the late twentieth century significantly altered the environment. Digital cameras provided the attraction of immediacy, allowing photographers to capture innumerable photos without the limitations of film. As a result, film sales began to plummet, and by the early 2000s, major film manufacturers had discontinued production of several film stocks. This move signalled the end of an era and the dawn of a new, digital-dominated era in photography.

Despite the overwhelming dominance of digital photography, a noteworthy counter-movement has formed over the last decade, marked by a renewed interest in analogue cameras and film photography. This comeback can be linked to a number of elements, including a desire for authenticity, a reaction to the disposable nature of digital photographs, and the distinct visual qualities that film offers.

In a world inundated with digital photos that are frequently altered, filtered, and edited, many photographers and consumers are looking for a more genuine form of expression. Film photography, with its naturalistic nature, conveys a sense of honesty and authenticity. Each frame contains the weight of intention as well as the medium’s unpredictable nature, resulting in a stronger connection between the photographer and their subject.

Furthermore, the tactile experience of shooting with a film camera, from loading film to manually adjusting settings, promotes a deep connection with the art form. This hands-on method contrasts dramatically with the convenience and detachment of digital photography, encouraging photographers to slow down and enjoy the process.

In today’s fast-paced environment, when photos are shared and devoured in seconds, the fleeting nature of digital photography has created a sense of disposability. Many people take thousands of photographs, yet only a few are printed or properly appreciated. This ephemerality contradicts the notion of photography as a tool of remembering and preservation.

Analogue photography, on the other hand, promotes intentional practice. Each shot on film is valuable and limited, as photographers are frequently limited to a roll of 24 or 36 exposures. This limitation encourages a focused and intentional approach, forcing people to consider composition, lighting, and subject matter before pressing the shutter.

Film photography’s inherent visual attributes help to fuel its resurgence. The grain, texture, and colour palette of different film stocks produce a distinct visual language that many photographers enjoy. Film’s faults can enrich photographs with character and passion, traits that are sometimes lost in the antiseptic accuracy of digital photography.

Many contemporary photographers have adopted this aesthetic, experimenting with various film stocks to obtain distinct appearances. For example, the warm tones of Kodak Portra 400, the brilliant colours of Fujifilm Velvia, and the great contrast of Ilford HP5 are all recognised for their distinct features. This innovation not only demonstrates film’s artistic potential, but it also connects modern photographers to the rich tradition of analogue approaches.

The resurrection of analogue photography has created a thriving community of film enthusiasts. Online platforms, social media groups, and dedicated forums let people to debate techniques, share their work, and even trade film and cameras. This sense of community strengthens the idea that analogue photography is more than just a trend, but a movement based on shared beliefs and experiences.

Workshops, meetings, and film festivals have also emerged, allowing photographers to network while also learning and collaborating. Events such as the “Film is Not Dead” festival and different film photography expos honour the medium while also providing a platform for budding artists to present their work.

Despite the increased popularity of analogue photography, numerous obstacles persist. Newcomers may face considerable difficulties due to film availability and increased processing costs. As a result, some photographers have turned to DIY processing techniques or sought out local labs that specialise in film development. However, the growing popularity of film has prompted some producers to reissue obsolete film stocks, ensuring that aficionados have a wide range of possibilities.

Furthermore, the environmental impact of film manufacturing and chemical processing raises ethical concerns. As photographers grow more aware of their environmental impact, conversations concerning sustainable methods in the analogue world are gaining steam. Initiatives aimed at reducing waste and encouraging environmentally friendly processing processes are critical to sustaining the viability of film photography as a medium.

The rebirth of analogue cameras is more than just a nostalgic yearning for the past; it reflects a significant cultural change towards authenticity, intentionality, and artistic experimentation. Photographers who appreciate the unique properties of film not only honour the medium’s rich heritage, but also contribute to its present progress.

This movement calls into question the idea that photography is solely a digital discipline, reminding us that the art form is multidimensional and ever-changing. The rebirth of analogue photography demonstrates the medium’s ongoing strength, emphasising the beauty of imperfection and the story contained within each frame. As we move forward, the blending of ancient and contemporary approaches will surely impact the future of photography, guaranteeing that digital and analogue coexist harmoniously, enhancing our visual culture for future generations.

Stone That Spoke The Secrets of Ancient Egypt

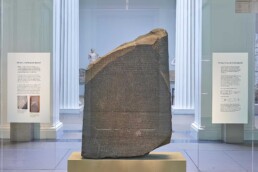

In 1799, amid the searing heat of the Egyptian summer and the tensions of Napoleon’s campaign in the region, an amazing discovery was discovered. A French soldier stationed near the town of Rashid (Rosetta) at the western mouth of the Nile Delta discovered a slab of granodiorite etched with ancient inscriptions. This artefact, subsequently known as the Rosetta Stone, was to transform our understanding of ancient Egypt, ushering in a period of decipherment and discovery that scholars had only imagined.

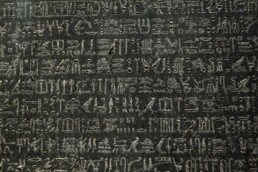

For decades, the ancient Egyptian language, hieroglyphics, had remained a mystery. Their elaborate emblems decorated the Pharaohs’ monuments and tombs, but their meaning was lost over time and cultural transition. However, the Rosetta Stone delivered the key to the lock. Through a fortuitous stroke of linguistic serendipity, the stone featured the identical passage in three different scripts: Greek, Demotic, and Egyptian hieroglyphs. This trilingual nature enabled scholars to ultimately decipher the hieroglyphic language code after years of laborious study.

The narrative of the Rosetta Stone begins in the context of imperial ambition. In 1798, Napoleon Bonaparte led a military expedition to Egypt, hoping to increase French power in the Middle East and establish a base of operations against British interests in the region. Along with his army, Napoleon recruited a team of historians, engineers, and scientists known as the savants, who were tasked with chronicling Egypt’s wonders, which had intrigued Europeans since Herodotus’ time.

The following year, Pierre-François Bouchard, one of Napoleon’s soldiers, accidentally discovered the stone while working on the foundations of a fort near Rosetta. Recognising its potential importance, the stone was promptly brought to the notice of French researchers. Following Egypt’s fall to British authority in 1801, the stone was transferred to the British Museum as part of the Treaty of Alexandria and is now one of the museum’s most cherished objects. The stone is roughly 44 inches high, 30 inches wide, and 11 inches thick, weighing around 760 kilogrammes (1,676 pounds). Though some of it is shattered, the inscription is still mostly legible.

The Rosetta Stone’s trilingual writings are from a decree issued by Egyptian priests in 196 BCE, during the reign of the Ptolemaic monarch Ptolemy V. The decree praised the youthful Pharaoh for being kind to the priesthood and sponsoring temples. The poem was written in three separate scripts—ancient Greek, Demotic (a reduced cursive form of Egyptian script used in daily business), and the hieroglyphic writing used for religious and ceremonial purposes—to ensure that it could be understood by Egypt’s numerous linguistic tribes.

The fact that the Greek language, which was well known among experts at the time, accompanied the ancient Egyptian letters on the stone was a huge breakthrough. Greek could be comprehended and translated, revealing the first significant hint to interpreting the cryptic hieroglyphs. However, it would take nearly two decades of intensive scholarly labour on a global scale before the entire significance of the stone was recognised.

Several renowned individuals in the early nineteenth century attempted to understand the Rosetta Stone’s markings, but two in particular stand out: English physicist Thomas Young and French linguist Jean-François Champollion. Young was the first to make significant advances. By 1814, he had demonstrated that part of the hieroglyphs were phonetic letters, which contradicted the widely held assumption that hieroglyphs were only symbolic. Young was able to recognise the names of Ptolemy and Cleopatra in the Egyptian script by comparing them to the Greek text. However, he failed to recognise that hieroglyphs might represent sounds across the entire Egyptian language.

Champollion, a linguist with a fondness for ancient languages, eventually made the key breakthrough. Building on Young’s findings and equipped with a thorough understanding of Coptic, a language descended from ancient Egyptian, Champollion discovered that the hieroglyphs had both phonetic and symbolic aspects. He announced in 1822, after years of diligent research, that he had deciphered the hieroglyphic script. This achievement was monumental not just because it unlocked ancient Egyptian language, but also because it led to a better understanding of Egyptian history, culture, and religion. His work was internationally acclaimed, and he is frequently regarded as the father of modern Egyptology. His decipherment of the hieroglyphs enabled researchers to read the previously inaccessible books, exposing a wealth of information about the pharaohs, their beliefs, and their civilisation.

The Rosetta Stone has since become a symbol of linguistic success and historical discovery. It had a profound impact on Egyptology. Scholars have pieced together a thorough history of ancient Egypt over millennia, from the Early Dynastic Period to the Greco-Roman era, by carefully studying hieroglyphic manuscripts. In addition to contributing to our understanding of ancient Egypt, the Rosetta Stone is a poignant reminder of previous cultures’ connection. The presence of Greek on the stone demonstrates the Hellenistic influence in Egypt following Alexander the Great’s conquests, yet the usage of Demotic emphasises the value of local Egyptian culture even under foreign rule.

Over time, the Rosetta Stone has evolved into a symbol of the power of knowledge and human creativity. The process of deciphering it was a collaborative, multinational endeavour comprising researchers from various countries and backgrounds working towards a shared aim. It demonstrates the everlasting interest with ancient Egypt and the yearning to understand humanity’s shared history.

Today, the Rosetta Stone is one of the most popular and beloved objects in the British Museum, with millions of visitors each year. Its value has stirred discussions about cultural heritage and antiquities ownership, with Egypt repeatedly requesting its return. While the stone’s physical presence is limited to the museum’s walls, its legacy and the knowledge it has revealed continue to resonate throughout the realms of archaeology, linguistics, and history. In current times, the name “Rosetta Stone” has even entered popular culture, representing the key to accessing previously inaccessible information. From language learning software to advanced scientific endeavours, the phrase connotes the victory of discovery and knowledge.

The Rosetta Stone is not only a key to understanding the ancient Egyptian language, but also a symbol of the pursuit of knowledge. Its discovery and following race to decipher its inscriptions were among the most significant intellectual triumphs of the nineteenth century, changing our view of one of the world’s oldest and most mysterious civilisations. Today, the Rosetta Stone piques our interest and inspires admiration, bridging the gap between the past and the present, providing insights into ancient worlds, and reminding us of humanity’s unending search for knowledge.

Phi and the Pursuit of Perfection in Visual Arts

The appeal of beauty has captivated humanity for generations, with countless minds wondering what makes something truly pleasing to the eye. Among the several hypotheses that have emerged, one stands out: the Golden Ratio. From the vast cathedrals of the Renaissance to the delicate balance of elements in a photograph, the Golden Ratio has inspired painters, architects, and photographers in their search of aesthetic perfection. This seemingly miraculous proportion, based on ancient mathematics, can be seen in nature, art, and the human body, serving as a link between the natural world and human creativity. Understanding the Golden Ratio in photography is like to discovering a hidden key to visual balance.

The Golden Ratio, represented by the Greek symbol φ (phi), has a value of around 1.618. The concept originated with ancient Greek mathematicians like as Euclid, who originally articulated it in his seminal work “Elements” approximately 300 BCE. However, Pythagoras established the foundation for its geometric study. The ratio happens when a line is divided into two pieces so that the longer part divided by the smaller part equals the total length divided by the longer part. This proportion was first detected in geometric shapes such as the pentagon and decagon, but its actual significance became clear when ancient architects began incorporating it into their works, particularly the Parthenon in Athens.

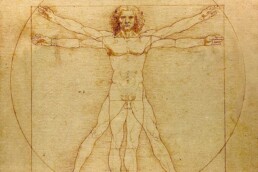

The Renaissance, an era of renewed interest in classical knowledge, propelled the Golden Ratio to the forefront of artistic development. Figures like Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Albrecht Dürer embraced the ratio and included it into the compositions of their works. The mathematical elegance of φ transcended its geometric beginnings, becoming a symbol of beautiful harmony and heavenly proportion in art. During this age, painters were captivated by proportion and symmetry, eager to discover the mathematical rules that govern beauty. Leonardo da Vinci’s classic artwork Vitruvian Man exemplifies how the Golden Ratio was applied to human anatomy. This artwork, which depicts a man inscribed in both a circle and a square, represents the Renaissance’s effort to explain the universe via mathematics and the human form. The proportions of the human body, as seen in this artwork, demonstrate the divine harmony inherent in nature.

Leonardo da Vinci’s picture The Last Supper displays the use of the Golden Ratio. Da Vinci methodically planned the construction of this renowned work, ensuring that important aspects of the narrative—the location of Christ and the apostles—were contained within areas established by the Golden Ratio. Similarly, Michelangelo used these concepts in his architectural designs, notably as the construction of St. Peter’s Basilica, which created spatial harmony by a careful application of phi.

This convergence of art and mathematics throughout the Renaissance was more than just a technical exercise. It was part of a larger intellectual movement that saw beauty as an expression of divine order. By sticking to these proportions, painters believed they were creating works that reflected the perfection of God’s creation, providing their audience with an experience of artistic transcendence.

While the Golden Ratio’s influence is frequently associated with big artistic movements from the past, its relevance has persisted into the current era, particularly in the art of photography. Photographers, like Renaissance artists, strive for images that are balanced, appealing, and engaging. In this pursuit, many people use the Golden Ratio to guide their compositions.

In photography, the Golden Ratio is represented by the Phi Grid and the Fibonacci Spiral. The Phi Grid is similar to the rule of thirds but more precise, dividing the frame into sections that follow the Golden Ratio. Placing subjects at these intersections produces a sense of natural equilibrium, guiding the viewer’s eye through the image in a planned yet simple manner. Unlike the rule of thirds, which divides an image into equal portions, the Golden Ratio’s asymmetry creates a subtle tension that heightens visual interest without overpowering the audience.

In contrast, the Fibonacci Spiral spirals outward from the smallest component of the image, increasing in size while keeping to the Golden Ratio’s proportions. Photographers utilise this spiral as a guide to arrange significant elements of their images along its path, resulting in a composition that organically leads the eye through the scene. This approach is especially useful in landscape photography, as natural components such as rivers, trees, or clouds can be placed to follow the spiral’s curve, creating a harmonic and full image.

Many of the world’s most prominent photographers have employed the Golden Ratio concepts in their work, either consciously or unconsciously. Henri Cartier-Bresson, often considered as the father of contemporary photojournalism, is one of these figures. Cartier-Bresson, famous for his “decisive moment” method, captured short moments that express tremendous human emotion and storytelling. While his images appear to be spontaneous, a close examination reveals that many of them are based on the Golden Ratio. The balance and flow of his frames create a rhythm that draws the viewer in while gently leading the eye across the image.

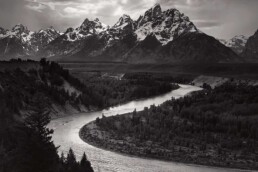

Another example is the American landscape photographer Ansel Adams, whose classic black-and-white photos of the American West still serve as genre benchmarks. Adams’ deep awareness of composition, along with his technical command of light, frequently produced compositions that followed the Golden Ratio. His landscapes, with their towering mountains, vast skies, and tranquil lakes, create a perfect balance that represents nature’s underlying mathematical order.

Understanding the Golden Ratio is one thing; putting it into practice is where the great power lies. Photographers wishing to incorporate this principle into their work have various options. Begin by visualising a Phi Grid or Fibonacci Spiral over your frame. Most current cameras and editing software include grid overlays that can assist in this process. When creating a shot, consider how to match your subject with the crossings or curves of these guides. This does not require mathematical precision; even approximating the Golden Ratio can result in more aesthetically pleasing visuals.

Landscape photographers can employ the Golden Ratio to add depth and movement to their photos. The composition becomes more dynamic by aligning the horizon with one of the Phi Grid lines or positioning a noteworthy element, such as a mountain peak or tree, at a key junction. Portrait photographers might use the Fibonacci Spiral to emphasise the subject’s face or eyes, directing the viewer’s attention to the image’s most essential features.

From the magnificent frescoes of the Renaissance to today’s digital screens, the Golden Ratio has served as an eternal pattern for beauty. Its use in photography serves as a reminder that visual art is more than just capturing moments; it is about organising materials in a way that communicates to something deeper within us. Whether through planned subject placement or the subtle flow of a composition, the Golden Ratio enables photographers to produce images that resonate with viewers on an almost subconscious level.

Understanding and adopting this ancient philosophy allows photographers to elevate their work, achieving a sense of balance, harmony, and beauty that goes beyond the ordinary. Just as Renaissance artists attempted to represent the divine in their work, modern photographers can use the Golden Ratio to create compositions that are eternal and universally appealing.