Beethoven's Symphony of Joy

The beautiful hills of Bonn, Germany, witnessed the development of one of history’s most transformative composers in 1770. A child prodigy, born to a court musician father, began his path in a chaotic environment, rather than with privilege. From a young age, this youngster was motivated by music, sculpted by hard discipline and a desire to transcend the ordinary.

The latter half of the eighteenth century was a period of colossal upheaval. Enlightenment ideals collided with existing regimes, resulting in uprisings across Europe. Against this setting, a young composer immersed himself in the Classical traditions established by Haydn and Mozart. Nonetheless, even in his early years, whispers of an unbreakable spirit and revolutionary flair distinguished him. This was no ordinary imitator; this was an artist destined to push the frontiers of music itself.

In an era ripe for revolution, grand symphonies, intimate sonatas, and ground-breaking concertos emerged. His Third Symphony, *Eroica*, originally dedicated to Napoleon Bonaparte, defied expectations with its audacious length and emotional depth. The Fifth Symphony, with its signature “fate knocking at the door” motif, is still one of the most recognised works in Western music. Piano sonatas such as the *Moonlight Sonata* and *Pathétique* demonstrate the depth of his contemplative brilliance.

Perhaps his best effort, the Ninth Symphony, concludes with the *Ode to Joy*, a choral climax that depicts global brotherhood—a feeling that continues to reverberate today. Such masterpieces were more than just compositions; they were expressions of human perseverance and transcendence.

Few incidents in the history of art are more heartbreaking and uplifting than the loss of a master composer’s hearing. Deafness began as a minor condition in his late twenties and gradually worsened, sinking him into despair. The renowned *Heiligenstadt Testament*, a letter he penned but never mailed, depicts his internal struggle: on the verge of death, he decided to live for his work. Against all odds, his disability fuelled his creativity rather than hindering it. During this period of intense quiet, Beethoven composed some of his most famous compositions, including the Ninth Symphony.

While widely honoured, his life was not without controversy. His volatile disposition, described by contemporaries as unpleasant and erratic, alienated many of those around him. Legal fights over custody of his nephew Karl revealed a very flawed but human side, characterised by possessiveness and domineering tendencies. Even romantic endeavours were plagued with heartbreak. The mystery of the “Immortal Beloved,” an unidentified character referenced in a passionate letter, continues to fascinate academics and fans.

Critics of his period were frequently divided, with some praising his creativity and others dismissing his drastic departures from norm. However, history has been clear in its assessment. His works provided the groundwork for the Romantic era, influencing figures such as Brahms, Wagner, and others.

The premiere of the Ninth Symphony in 1824 was one of the most melancholy occasions of his life. Unable to hear the thunderous clapping, he reportedly turned around to see the audience’s overwhelming adulation. This one event represents not just creative accomplishment, but also human tenacity in the face of enormous circumstances.Another defining event was his funeral in 1827. Over 20,000 people packed the streets of Vienna to say goodbye, demonstrating his great influence on his contemporaries and the musical world.

His works continue to have a profound impact across genres, civilisations, and centuries. His compositions have appeared in a variety of settings, including grand orchestral concerts, film scores, advertisements, and pop music. The *Ode to Joy* serves as the European Union’s anthem, representing ideals of unity and peace.

Modern interpretations of his life and work continue to flourish, ranging from biographies and films to academic research that reveals new insights into his creative processes. For many, his life story exemplifies the limitless potential of human ingenuity, especially in the face of tragedy.

The capacity to connect across time is what distinguishes a genius, and this composer’s music does just that. His compositions encourage listeners to go into the depths of emotion, the heights of human aspiration, and the beauty of artistic inventiveness. In an ever-changing world, his music serves as a constant, a bridge to the sublime that reminds us of our common humanity.

The Rhythms and Colours of Naga Legacy

Every December, a spectacular celebration takes place in the undulating hills of Nagaland, India, attracting visitors and culture aficionados from all over the world. The Hornbill Festival, named after the beloved bird fundamental to Naga culture, is more than just a demonstration of traditions; it is a celebration of legacy, tenacity, and unity.

Long before the celebration became an annual spectacle, Nagaland’s numerous tribes performed their customs and rituals independently. Each tribe, from the Ao to the Konyak, protected their distinct traditions, art forms, and dialects. Recognising the importance of preserving and sharing this cultural heritage, the Nagaland government established the Hornbill Festival in 2000. Conceived as a cultural fusion, the festival aims to unite the state’s 16 tribes while also promoting tourism and the region’s rich legacy.

The event is named after the hornbill, a mystical bird in Naga culture that represents prosperity and legend. It also represents the Naga tribes’ affinity to nature, since the hornbill is frequently depicted in traditional jewellery, dances, and storytelling.

A sensory feast awaits visitors to Kisama Heritage Village, the festival grounds, as soon as they enter. The air is filled with the rhythmic pounding of log drums, interspersed with the sounds of tribal music. Each tribe sets up its own morung—a traditional house that serves as a cultural pavilion—to give tourists a look into their way of life. These carefully built structures serve as centres for storytelling, music, and artisan demonstrations, bridging the gap between past and present.

Traditional dance performances are among the festival’s most engaging attractions. Dancers, dressed in intricate costumes made of feathers, beads, and vivid textiles, move in sync while recounting stories of valour, romance, and harvest. These performances are more than just creative manifestations; they are profoundly ingrained in the tribes’ spiritual beliefs and collective identity.

The aroma of traditional Naga cuisine permeates the festival grounds, enticing visitors to sample the region’s rich flavours. The delicacies, which range from smoky pork with bamboo shoots to spicy axone (fermented soybean) chutney, represent the Naga people’s inventiveness and strong attachment to their land. Adventuresome foodies frequently sample uncommon dishes such as silkworm larvae and snails, demonstrating Nagaland’s wide culinary heritage.

Local rice beer, produced in traditional earthen pots, flows freely and adds to the joyous atmosphere. Sharing a cup of this earthy drink is widely used as a bonding ritual between residents and guests, breaking down linguistic and cultural boundaries.

While the Hornbill Festival is a celebration of heritage, it also demonstrates Naga culture’s persistence in the face of modernity. The festival allows indigenous craftsmen to demonstrate their crafts, ranging from finely woven shawls to hand-carved wooden sculptures. These masterpieces not only conserve traditional traditions, but they also benefit the local economy by empowering craftspeople to maintain their history.

In addition to cultural performances, modern events like rock concerts, fashion exhibitions, and motor rallies illustrate Nagaland’s developing character. The blend of traditional and modern features demonstrates Naga society’s versatility, honouring both its origins and its future goals.

The Hornbill Festival has evolved into a symbol of solidarity not only for the people of Nagaland, but also for India’s northeast. It has drawn global attention to the state, boosting sustainable tourism and fostering a better appreciation of its distinct culture. However, the festival raises concerns about the commercialisation of traditions. The organisers continue to struggle with striking a balance between keeping authenticity and adjusting to current demands.

For Nagaland’s tribes, the festival is more than just a cultural display; it is a reaffirmation of identity in a rapidly changing world. The Hornbill Festival guarantees that the Naga people’s legacy lives on by passing down songs, stories, and traditions to future generations.

The Hornbill Festival is more than a tourist attraction; it also functions as a cultural bridge. It invites visitors to immerse themselves in Nagaland’s rhythms, colours, and flavours, establishing connections across geographical and cultural borders. Each December, Kisama Heritage Village transforms into a vivid tapestry of people, with customs embraced, memories shared, and a sense of community reigning.

The festival’s echoes reverberate long after it ends, leaving visitors with a deep understanding for the Naga culture. In the midst of the hills, the Hornbill Festival serves as a timeless reminder of the beauty of diversity and the enduring force of cultural history.

The Euro Dream A Currency Without Borders

The Euro, born out of a goal for unification, is more than just a currency; it epitomises a continent’s hopes for harmony. Its adoption in 1999 was more than just a financial milestone; it was also a geopolitical manoeuvre to strengthen European integration in the aftermath of a century marked by separation and conflict. The Euro’s tale is one of ambition, resistance, and significant worldwide impact.

The seeds of a common European currency were sown in the aftermath of WWII. Devastated economies and shattered alliances prompted leaders to seek unprecedented cooperation. Early efforts, such as the European Coal and Steel Community in 1951, paved the way for greater integration. By the 1980s, the European Economic Community (EEC) hoped to eliminate currency instability, which was a key impediment to a single market.

Momentum escalated with the Maastricht Treaty of 1992, which formed the European Union (EU) and paved the way for a unified currency. Leaders such as Jacques Delors and Helmut Kohl promoted the Euro as a symbol of a unified Europe, transcending national identities to form a coherent economic powerhouse. However, this idea was not without its adversaries.

Resistance to the Euro was strong and broad, expressing concerns about losing national sovereignty. Sceptics contended that countries with various economies and fiscal policies couldn’t survive in a one-size-fits-all monetary system. For countries like Germany, which is known for its budgetary discipline, sharing a currency with less secure economies like Greece aroused concerns about economic risk. Meanwhile, cultural attachments to national currencies, such as the French franc or the Italian lira, sparked visceral hostility among residents.

The 2008 financial crisis revealed vulnerabilities in the Eurozone, reigniting debate about its survival. The sovereign debt crisis in Greece, which pushed the country close to bankruptcy, put the EU’s resolve to the test and exposed systemic flaws. Critics blamed the crisis on a lack of fiscal union, which allowed countries to share a currency but maintain independent budgets.

As a geopolitical tool, the Euro increased the EU’s global power, threatening the supremacy of the US dollar. It strengthened member states’ bargaining power in international trade and finance. However, its strength has also drawn criticism. Some saw the Euro’s rise as a threat to dollar hegemony, which sparked geopolitical rivalry.

Internally, the Euro became a litmus test of European cooperation. Brexit in 2016 highlighted growing discontent within the EU, notwithstanding the UK’s retention of the pound sterling. Euroscepticism soared in countries such as Italy and Hungary, where economic difficulties fuelled criticism of EU policies, notably the limits of the single currency.

Externally, the Euro’s stability has become a two-edged sword. Nations outside the Eurozone, notably in Eastern Europe, faced the difficult decision of entering or remaining independent. While inclusion provided economic connectivity, it also required tough reforms, causing conflict in countries already undergoing post-Soviet transitions.

The Euro is still a work in progress, an experiment in integrating various nations behind a common economic agenda. Despite its problems and obstacles, it has unmistakably altered Europe’s financial environment and global position. It connects economies, promotes trade, and boosts the EU’s position on the global arena, even as it faces continuous challenges.

As Europe faces a fast changing world—climate change, technological upheaval, and shifting power dynamics—the Euro’s future is likely to reflect the strength of the unity it represents. Its voyage serves as a reminder that, while beset with challenges, economic and political integration remains a strong weapon for creating a more integrated and cooperative world.

In the end, the Euro is more than simply a currency; it represents a continent’s willingness to overcome its divisions and embrace a common destiny. Its continued success will be determined by Europe’s states’ long-term commitment to their shared vision.

Climate-Proof Your Style with the Right Jacket

As the biting bite of December’s chill settles across much of the Northern Hemisphere, travellers are reminded of the value of careful planning. The jacket, an essential companion for travellers, becomes more than just a clothing; it’s a protective layer against the weather and a symbol of adaptability. With temperatures ranging from icy polar winds to temperate rainforests, choosing the correct jacket necessitates both strategy and an awareness of what distinguishes each region.

Embracing Frost: Jackets for Winter Wonderland Adventures

Imagine entering a snow-covered environment with temperatures dropping to sub-zero levels. In these circumstances, insulation is your best friend. Down coats, stuffed with goose or duck feathers, have excellent warmth-to-weight ratios and trap heat efficiently. Synthetic insulated jackets, on the other hand, are great for damp cold, as moisture can damage down’s insulating characteristics. Look for exterior shells with water-repellent coatings to defend against snow and sleet.

Layering is quite important in this context. Combine a mid-layer fleece or wool jumper with a waterproof and windproof outer shell to provide adaptable warmth. Winter coats with adjustable hoods and snow skirts provide extra protection, preventing sneaky drafts while exploring ice caves or ski slopes.

Battling Rain and Wind: The Need for Waterproof Shells

Staying dry becomes a problem in rainy areas such as Norway’s misty fjords or the Pacific Northwest’s verdant landscapes. Waterproof jackets, especially ones with GORE-TEX or comparable membranes, are invaluable. These high-tech textiles keep water out while allowing sweat to leave, eliminating the clammy feeling after a strenuous walk.

Lightweight rain shells with adjustable cuffs and hem cinches allow trekkers to move around freely. For urban travellers, trench-style raincoats with a modern appeal mix utility and fashion, keeping you dry while you meander through cobblestone streets in the drizzle.

How to Survive in the Tropics: Humidity and Sudden Storm Jackets

Tropical areas present their own set of issues, including unpredictable rain showers and excessive humidity. Choose breathable and lightweight coats with water resistance rather than full waterproofing, as ventilation is critical to avoiding overheating. Softshell jackets with moisture-wicking characteristics can protect you from sudden rain and mosquito bites on jungle trips.

Temperatures in high-altitude tropical places, such as the Andes, can decrease significantly after sunset. A packable insulated jacket is a sensible solution that combines compactness with warmth on chilly nights.

Navigating the Desert: Where Heat Meets Chill

Deserts are a study in extremes, with blistering heat during the day and bone-chilling cold at night. A adaptable jacket is required to handle these quick variations. Lightweight and sun-resistant materials protect against UV exposure during the day, while a packable insulated jacket or fleece layer keeps you toasty after the sun goes down.

Wind is another aspect to consider in desert environments. Look for windproof jackets with high collars and elasticised cuffs to keep out sand and grit brought by sudden gusts. Neutral colours, such as beige or khaki, reflect sunshine and keep you cool during the day.

Mastering the Mountains: Equipment for High-Altitude Explorations

Mountain weather is typically erratic, with brightness swiftly giving place to thunderstorms. Layering is an absolute necessity in such contexts. Begin with a moisture-wicking base layer to regulate sweat, then add an insulating midlayer like fleece or synthetic down. The outermost layer is a durable hardshell jacket designed to endure high winds and precipitation.

Look for jackets with alpine-specific features, such as pit zips for ventilation during steep ascents, helmet-compatible hoods for climbers, and reinforced panels for toughness against rock scrapes. Bright colours are a sensible choice for improving visibility in an emergency.

Adapting to Transitional Seasons: Jackets for Mild Climates

Spring and fall necessitate adaptability, as temperatures can fluctuate considerably during the day. A three-in-one jacket, which includes a detachable warm layer and a waterproof outer shell, is an excellent travel companion. This modular design enables you to adapt fast, whether you’re basking in morning sunshine or fighting an unexpected afternoon downpour.

A beautiful peacoat or wool blazer is ideal for nighttime outings in cities during transitional seasons, providing a blend of warmth and sophistication while remaining practical.

Fine-tuning the Fit: A Traveler’s Checklist

Choosing the proper jacket is about more than simply the weather; it’s also about comfort and utility. Ensure that the fit allows for layering, particularly in colder climates. Adjustable features such as cuffs, hems, and hoods provide both customisation and protection. Pockets are a traveler’s secret weapon; look for designs with many pockets to store items such as gloves, maps, and snacks.

Choice of fabric is also important. Natural fibres, such as wool, excel at keeping warmth, whilst synthetic materials have excellent water resistance and quick drying capabilities. For extended trips, prioritise jackets that are packable, allowing you to reduce space in your luggage while being prepared.

The Journey’s True Companion

Every climate has unique requirements, and each jacket tells a story. Whether you’re fighting Arctic storms, wandering through tropical rainforests, or navigating crowded cities, the apparel you wear can make or break your experience. The best jackets are those that perfectly merge utility and the spirit of exploration, evoking the modern traveler’s tenacity and versatility.

The cold weather in December calls for adventure. Allow your jacket to be more than just a need as you go on your journey—it will reflect your wanderlust, serve as a symbol of readiness, and be your ally in embracing the world’s ever-changing environment.

Capturing Life’s Moments One Frame at a Time with Adi Pranoto

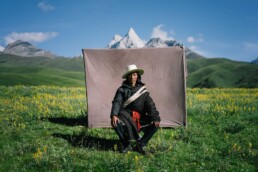

Photography is an art form that captures moments in time and allows us to revisit them over and over. Some people like it as a hobby, while others consider it a way of life. In this interview, we speak with a company owner, Adi Pranoto, who has become an avid photographer, and his path through photography is as inspiring as the photographs he creates. From street photography on business trips to exploring cultural landscapes and human connections, his tale is one of curiosity, enthusiasm, and the pursuit of significant experiences.

Who are you, and how did your passion in photography start?

I am the owner of Cobra Dental, a distributor of dental goods and tools. My passion in photography arose from numerous excursions to suppliers in many cities and nations. I typically chronicled these visits using street photography. Now that I have entrusted the business to my children, I have more time to dedicate to my passion.

What was your most memorable trip with Mahacaraka®, and why?

Each journey with Mahacaraka has been memorable. These visits have been extremely rewarding for me because of the experiences I’ve received and the wonderful images I’ve taken.

What is your favourite photo from a Mahacaraka® tour and why?

My fave photograph is of Pasola. Prior to joining Mahacaraka, I attempted to photograph Pasola under the supervision of Romo Efrem (†), who is well-known in the community. Despite his assistance, I could not acquire a good shot. However, with Mahacaraka’s supervision, I was able to acquire several stunning images, including portraiture, street shots, documentary, panning, and action shots.

Have you ever considered turning photography into a business, such as selling your work or becoming a professional photographer? Why ?

For the time being, I am pleased with my hobbies. I prefer to avoid the complexity of professionalism, such as learning sophisticated procedures, using equipment, post-processing, and managing data.

Who or what inspires you in photography?

My grandmother. During my school years, I lived with her in the village and learnt life philosophies and principles that I still cherish. Her ideas on social interaction, religious life, and balance influence how I capture life with my lens.

Which photographic genre are you interested in researching further, and why?

I’m getting ready to try bird photography because I have a few possibilities coming up. I’ve already purchased the necessary equipment, including a sufficient focal length lens.

Have you ever considered turning photography into a business, such as selling your work or becoming a professional photographer? Why ?

For the time being, I am pleased with my hobbies. I prefer to avoid the complexity of professionalism, such as learning sophisticated procedures, using equipment, post-processing, and managing data.

What is your favourite photography genre? What attracts you to it?

I don’t have a certain genre yet, but human interest photography is especially appealing and hard. It frequently necessitates rapid decisions to capture the proper moment.

Who or what inspires you in photography?

My grandmother (†). During my school years, I lived with her in the village and learnt life philosophies and principles that I still cherish. Her ideas on social interaction, religious life, and balance influence how I capture life with my lens.

How do you retain physical stamina and endurance for trip photography, especially given your age?

Reflexes and physical strength suffer as people get older. I carefully choose destinations that are suitable for my physical ability. Regular exercise, adequate relaxation, a balanced diet, and keeping cheerful are essential for preserving my fitness.

If you could only use one lens, which would it be and why?

I’d go with a 35mm lens because it allows for proper framing without distortion.

What is your dream destination, and why?

I have numerous dream destinations: Nias for its fascinating culture, Wakatobi and Derawan for their natural beauty, Badui Dalam for its distinct community life, Bali for its rich culture, and Timika for its festivals. Internationally, I would like to visit Pakistan, Iran, Mexico, and Antarctica.

Could you explain your photographic style?

Relaxed and quite spontaneous.

What do you appreciate best about photography, and why?

I adore documenting events or objects that reflect my life experiences. It’s a means to compare them to current realities.

What is the most difficult challenge you’ve faced in photography, and how did you overcome it?

The most difficult challenge has been the physical strain of transporting equipment and travelling to remote sites. I typically employ porters or use vehicles to get as near to the place as possible.

How do you interact with your subjects, especially when photographing them?

I start with a pleasant gesture, such as holding the camera at chest level while smiling. If they appear amenable, I engage in light chat before shooting the shot. If they express discomfort, I respect their boundaries and do not proceed.

Are there any other creative forms that inspire your photography? If so, which ones?

No, I haven’t found any other art forms to inspire my photography.

Through this interview, it is clear that photography from Adi Pranoto’s perspective is more than just capturing photographs; it is also about weaving tales, connecting with people, and cherishing life’s precious moments. His experience demonstrates the power of passion and perspective. Whether discovering cultural diversity, indulging in nature, or recalling cherished memories, photography remains a meaningful and gratifying activity. It’s a gentle reminder that the beauty of life is frequently found in the small aspects that we take time to enjoy.

Exposure Modes as the Photographer’s Compass

The art of photography has always been a dialogue between light and shadow, dating back to the early nineteenth century when the earliest photographers experimented with light-sensitive materials. The progress of cameras over the decades has provided us with tools that make obtaining the perfect image easier, yet the interplay of light remains a fundamental issue. Among these instruments, exposure modes have served as a compass to help photographers navigate the difficulties of light control.

In the early days of photography, every shot was meticulously calculated. Pioneers like Louis Daguerre and Henry Fox Talbot used intuition and experimentation to calculate exposure times. As cameras became more advanced, mechanical shutters and light meters were developed in the twentieth century, opening the door for the first exposure modes. By the mid-1900s, cameras such as the Leica M3 and Nikon F provided photographers with more control, including settings that automated some aspects of exposure. These advances were not just technological milestones, but also conceptual shifts that allowed photographers of all ability levels to express themselves creatively.

Shutter speed, aperture, and ISO are the three major elements that contribute to exposure. Each plays an important part in controlling how much light reaches the camera sensor, influencing both the technical and artistic qualities of the image. Exposure modes are essentially preset sets that simplify or improve control over these variables while customising them to specific conditions.

Modern cameras typically have four main modes: program (P), aperture priority (A/Av), shutter priority (S/Tv), and manual. Each has a distinct personality that is well-suited to various shooting settings and creative concepts.

Program Mode: A Versatile Companion

Flexibility is essential when dealing with unanticipated situations. Program mode is often compared to an all-purpose tool that automatically balances aperture and shutter speed. While it eliminates the guesswork from exposure, it does allow for modifications such as ISO and exposure compensation. This mode works best in casual scenarios like street photography or family gatherings, where time is of the essence.

However, relying too heavily on automation can lead to less creative control. When utilising Program mode, consider fine-tuning your settings to match the mood of your shot, so it doesn’t become too generic.

Aperture Priority: The Artistic Lens

Depth of field can tell a story, from isolating a subject against a creamy background to bringing a full landscape into perfect focus. Aperture Priority mode is the preferred setting for photographers who want complete control over the aperture. Setting the f-stop manually causes the camera to alter the shutter speed, resulting in the desired exposure.

This setting is ideal for portraiture, where a wide aperture (e.g., f/2.8) softens the background and draws emphasis to the person. It’s as effective in landscapes, where narrower apertures (e.g., f/11 or f/16) keep all elements clear and distinct. However, in poor light, slower shutter speeds might cause motion blur. Using a tripod or boosting the ISO can reduce this risk.

Shutter Priority: Freezing or Blurred Time

Precision is required during movements. Shutter Priority mode allows you to control the narrative of time, whether you want to freeze the splash of a breaking wave or emphasise the velocity of a speeding car. By specifying a shutter speed, the camera adjusts the aperture to ensure optimum exposure.

This setting is essential for sporting, wildlife, and action photography. A rapid shutter speed (e.g., 1/1000s) freezes dynamic action, but slower rates (e.g., 1/30s) create purposeful motion blur, giving the image a sense of flow and vitality. Challenges emerge in low-light conditions, where the aperture may not expand wide enough to compensate, resulting in underexposure. In such instances, boosting the ISO or using artificial lighting becomes necessary.

Manual Mode: Ultimate Mastery

Manual mode provides unfiltered canvas for those seeking maximum creative control. The photographer controls all aspects of exposure, including shutter speed, aperture, and ISO. This mode necessitates a thorough awareness of light and the capacity to respond swiftly to changing situations.

Manual mode is extremely useful in studio photography, astrophotography, and other situations where consistency is essential. It enables for fine adjustments to get the desired effect, such as capturing the subtle interplay of light and shadow in a still life or the vivid colours of a starry night. However, it can be intimidating for beginners, and the risk of over- or underexposure increases without careful control of the camera’s light meter.

Choosing the Correct Mode for Each Scene

Understanding when to use each mode shifts a photographer’s role from passive spectator to active storyteller. Below are some common scenarios and suggested modes:

Portraits: Use Aperture Priority with a wide aperture (f/1.8-f/4) to get gentle background blur.

Landscapes: Use Aperture Priority with a narrow aperture (e.g., f/11-f/16) to ensure sharp focus throughout.

Action or Sports: Use Shutter Priority with a fast shutter speed (e.g., 1/1000s or faster) to freeze motion.

Night Photography: Use manual mode to precisely regulate lengthy exposures and low ISO settings.

Casual or street photography: Use program mode to make quick modifications in dynamic conditions.

Today’s cameras, with improved algorithms and AI-powered capabilities, push the limits of what exposure modes can do. Auto ISO, face identification, and scene recognition enhance the photographer’s ability to adapt to challenging lighting conditions. While these improvements make photography more accessible, they also present photographers with the problem of maintaining their artistic voice in the face of automation.

Mastering exposure modes is more than simply technical ability; it is about knowing light as a storyteller. Each mode, with its own set of strengths, becomes a tool for recording memorable moments. As photography evolves, the principles of exposure remain constant, reminding us that the interplay between light and shadow is eternal while still being accessible to new interpretation.

The Nostradamus Effect: Belief, Skepticism, and Mystery

Michel de Nostredame, a young apothecary’s son, was born in 1503 in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, France, and went on to become one of history’s most mysterious individuals. The Renaissance-era physician, astrologer, and author wrote cryptic quatrains in his magnum opus, “Les Prophéties”, a work that continues to pique interest and provoke controversy centuries after its publication in 1555. Nostradamus’ origins were entrenched in a mixing pot of Jewish history, scientific inquiry, and mysticism, all of which created his distinctive worldview and fuelled his disputed predictions.

Following a period of plague and ecclesiastical strife, the seer studied medicine at the University of Avignon and later Montpellier. His work as a healer during the Black Death established him as a man of science, but his interests soon shifted to the celestial. By studying planetary alignments and interpreting ancient texts, Nostradamus developed a prophetic technique that combined astrology with a thorough understanding of historical cycles. This duality—scientist and mystic—became the defining feature of his life and career.

Some of the 942 quatrains in “Les Prophéties” have been regarded as predictions of key world events. One of the most often reported prophesies states:

“From the depths of the West of Europe, A young child will be born of poor people, He who by his tongue will seduce a great troop; His fame will increase towards the realm of the East.”

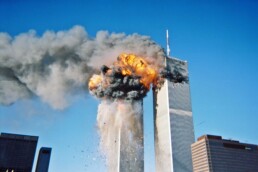

This quatrain is frequently attributed to Adolf Hitler, despite its ambiguous phrasing that allows for interpretation. Another intriguing case cites “two steel birds” dropping from the sky, which some have linked to the 9/11 attacks. While these interpretations pique the interest, others contend that the wording is so imprecise that it may be modified to fit almost any noteworthy event.

The attraction of his work stems from its obscure nature, yet detractors have long rejected Nostradamus’ forecasts as nothing more than lyrical riddles. Deciphering the scholar’s aim is difficult due to his use of metaphor, anagrams, and cryptic references, which frequently leads to drastically divergent interpretations. Sceptics further point out the post-hoc nature of his claimed accuracy, stating that many linkages to historical events were drawn after the events had transpired.

In the internet era, Nostradamus’ quatrains have gained a new audience. Social media platforms and online forums are full with allegations relating his work to current challenges ranging from climate change to artificial intelligence. Some admirers believe his forecasts foreshadow a worldwide battle or perhaps extraterrestrial contact. Conspiracy theories abound, with some claiming that his writings include a hidden code designed to lead humanity through turbulent times.

However, these interpretations frequently exhibit cherry-picking and confirmation bias, ignoring the larger context of his work. Scholars warn against taking these assertions at face value, demanding a more critical assessment of his legacy.

Despite the scepticism, Nostradamus is still a cultural figure. His legacy goes beyond prophecy to literature, film, and art, where his enigmatic presence and perplexing quatrains continue to inspire imaginative interpretations. For believers, he is a visionary whose ideas transcend time. For sceptics, he represents humanity’s attempt to find meaning in the chaos of history.

Nostradamus’ aura stems from his continuing relevance rather than his ability to accurately foresee the future. Whether viewed as a prophet or a poet, his quatrains act as a mirror, reflecting our worries, hopes, and never-ending search for insight in an uncertain world.

Conquering the South Pole and Our Limits

For generations, explorers, scientists, and adventurers have been intrigued by the South Pole’s vastness and untamed nature. This enigmatic frontier played host to one of history’s most dramatic and daring sagas, the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration, in the early twentieth century. This era was distinguished by bravery, resourcefulness, and sheer willpower, culminating in one man’s victorious arrival at the Earth’s southernmost point. This accomplishment, headed by Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen, changed our understanding of the Antarctic and left a lasting legacy of inspiration.

Human curiosity with Antarctica peaked in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, when the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration began in earnest. With minimal technology and little understanding of the frozen continent, explorers set sail to trace its coasts, research its icy innards, and uncover its mysteries for scientific and national glory. The South Pole, an invisible spot defined only by latitude and longitude, became a prized possession—a symbol of humanity’s triumph against nature’s harshest elements.

Between 1901 and 1922, pioneers such as Ernest Shackleton, Robert Falcon Scott, and Roald Amundsen pursued their goals relentlessly. These explorers endured incredible difficulties, including blinding blizzards, skin-freezing temperatures, and solitude that pushed the limits of human endurance. Nonetheless, their determination ushered in a new era of polar exploration, laying the framework for humanity’s first foray into the icebound heart of Antarctica.

Vision, planning, and adaptability marked the commander who would eventually triumph in the hunt for the South Pole. Roald Amundsen, born in Norway in 1872, was an experienced Arctic explorer who had made a name for himself by traversing the Northwest Passage. By 1910, his concentration had turned southward. Unlike those who had failed before, Amundsen approached the Antarctic with rigorous preparation. His strategy was efficiency, relying on sled dogs (a skill learnt by studying the indigenous Inuit people of the Arctic) and choosing a path with fewer topographical barriers.

The expedition to the South Pole began aboard the ship Fram, which was specifically equipped to endure polar conditions. Under Amundsen’s direction, his party meticulously prepared supply depots and worked relentlessly to acclimatise themselves to the harsh Antarctic conditions. Their efforts paid off. On 14th December 1911, Amundsen and four of his men raised the Norwegian flag at the South Pole, marking the first time humanity had set foot on this frozen axis of the globe. Their return journey was as successful, demonstrating the mission’s outstanding planning and execution.

In the Antarctic, triumph was frequently juxtaposed with tragedy. Only weeks after Amundsen’s triumph, Robert Falcon Scott’s British expedition reached the South Pole, only to discover that they had been defeated. Scott’s squad, weakened by poor preparation and dependence on ponies rather than dogs, perished from malnutrition and exposure during their perilous return. This dichotomy of success and failure highlighted the crucial significance of planning, adaptation, and respect for the harsh Antarctic environment.

Decades after Amundsen’s revolutionary feat, the expedition’s impact is being felt today. The expedition to the South Pole highlighted the incredible possibilities of human resolve and inventiveness. It also sparked a broader interest in polar studies, inspiring future scientists and explorers to investigate Antarctica’s distinct ecosystems, ice sheets, and climatic systems.

Today, the South Pole is no longer an inaccessible border. Modern facilities, such as the Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station, have transformed it into a centre for scientific research. Researchers stationed there delve into a variety of subjects, from astrophysics to climate science, uncovering discoveries that influence global policies and our understanding of Earth’s past and future. The Antarctic Treaty of 1959, an international pact aimed at the peaceful and cooperative usage of the continent, exemplifies the lasting spirit of discovery and collaboration that emerged during the Heroic Age.

Standing at the South Pole reminds one of the fortitude required to reach there over a century ago. Amundsen’s achievement is not just a historical milestone, but also a lasting symbol of human perseverance and innovation. The frozen expanse that once defied exploration is now a canvas for scientific discovery and a sobering reminder of our planet’s fragility.

The saga of the South Pole is far from over. The problems change with each generation, but the allure stays the same. As the freezing winds sweep across the desolate continent, they carry whispers of the past—of men and women who dared to dream of the unthinkable and made it happen.

A Fateful Sunday Morning in Pearl Harbour

The early twentieth century was a period of tremendous development and rising tension. In the Pacific, a developing empire and an established international power were quietly but slowly preparing for an inevitable battle. Japan, an industrial and military giant, aimed to expand its influence in Asia and the Pacific. The United States, on the other hand, maintained its control in the region by establishing strategic naval stations that functioned as both defensive strongholds and warnings to potential attackers. Among these, the harbour on Oahu, Hawaii, stood out—not only because of its position, but also for its symbolic and strategic significance.

Pearl Harbor’s strategic location made it significant even before the bombing. Located near the centre of the Pacific, it was an ideal location for the United States to project power and safeguard its Pacific territories, particularly the Philippines and Guam. However, Pearl Harbour posed a danger to Japan’s objectives in Southeast Asia and the Pacific islands. Controlling this key canal was critical to Japan’s ability to dominate the Pacific theatre without intervention.

Plans for an attack did not form overnight. They were the culmination of decades of antagonism and opposing interests. Japan’s expansionist actions in Manchuria, China, and subsequently French Indochina spurred the United States to impose economic restrictions and embargoes, particularly on oil, a crucial resource for Japan’s war machine. Desperate to grab resources and consolidate control, Japanese officials planned a decisive blow—one that would cripple the United States Pacific Fleet and allow Japan to solidify its gains.

On 7th December 1941 started like any other Sunday. Sailors relaxed, officers went to church, and the busy naval base hummed with bustle. Unbeknownst to those on the ground, six Japanese aircraft carriers lay just north of Hawaii, launching waves of fighters, bombers, and torpedo planes in the early morning darkness.

As the first planes fell on Pearl Harbour, confusion and incredulity spread across the ranks. The legendary battleship USS Arizona was among the first to receive a direct hit, culminating in a huge explosion that confirmed its destiny. Nearby, the USS Oklahoma sank after receiving numerous torpedo strikes, trapping hundreds of men within. In barely 90 minutes, havoc ensued, with approximately 2,400 people killed, over 1,000 injured, and dozens of ships and planes destroyed or severely damaged.

The ingenuity and precision of the attack stunned the world. For many Americans, the image of the Arizona sinking or the black plumes of smoke rising from the harbour were etched in their collective memory—a defining moment of vulnerability and resolve.

The selection of Pearl Harbour as a target was strategic and symbolic. Militarily, the harbour housed the United States Pacific Fleet, which posed the most significant challenge to Japanese goals in the Pacific. A severe blow to the fleet would give Japan valuable time to solidify its positions and strengthen its defences against any American counterattacks.

Pearl Harbour symbolised American dominance in the Pacific. Striking it was both a tactical and psychological manoeuvre, with the goal of demoralising both the US troops and the American people. However, Japan overestimated its adversary’s resilience.

The attack on Pearl Harbour not only brought the United States into World War II, but also constituted a watershed moment in global history. On 8th December 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt delivered his memorable “Day of Infamy” speech, inspiring a bereaved but determined nation to act. Congress declared war on Japan within hours, with Germany and Italy following suit days later. The fight, which had previously been confined to Europe and Asia, had now evolved into a global war.

The immediate aftermath of Pearl Harbour was dismal. The Pacific Fleet was seriously damaged, and the US military raced to recover. However, the attack galvanised the American people, resulting in an increase in enlistment and a sense of national unity that few events had previously. Over the next four years, the United States would use its industrial and military strength to shift the tide of the war in conflicts such as Midway and the Philippines.

Today, Pearl Harbour serves as a solemn reminder of the costs of war and a nation’s resilience. The USS Arizona Memorial, which sits above the sunken battleship, is a powerful reminder of sacrifice and perseverance. Thousands of people visit the site each year to pay their respects to those who have died and to reflect on historical lessons.

The events of 7th December 1941, altered not only the direction of the war, but also the geopolitical landscape of the twentieth century. They served as a vivid reminder of the delicate balance of peace and the devastation caused by violence. Looking back, Pearl Harbour is more than just a historical event; it is a story of sorrow, resolve, and transformation that has been inscribed into the world’s collective memory.

Walt Disney The Architect of Everlasting Fantasies

In the early twentieth century, a young dreamer with a talent for drawing began to shape what would become a watershed moment in the entertainment industry. Born on 5th December 1901, in Chicago, Illinois, this creative spirit grew up with a passion for storytelling and painting. During his formative years in Missouri, he developed an interest in drawing and painting, often inspired by the natural environment around him. These humble beginnings established the groundwork for a worldwide empire that would last decades.

The childhood years were characterised by modest lifestyle. Raised in a household of five children, he learnt the importance of hard work and perseverance from his strict yet hard-working father. His early mornings were spent working on a paper route, but his enthusiasm for drawing persisted. Enrolling in art school at a young age helped his skills improve, but recognition remained years away. Moving to Kansas City in his teens, he got work as a commercial illustrator, which was his first foray into the creative sector.

An opportunity to explore with animation technologies inspired an idea that would alter the course of his career. Working with his brother Roy, he developed the Laugh-O-Gram Studio, which, while inventive, struggled financially. Bankruptcy forced its closure, yet the setback did not put out the fire within him. When he moved to California, he reunited with Roy and founded a modest studio that would eventually hold their family name. The creation of Mickey Mouse in 1928 signalled the start of a revolution, with “Steamboat Willie” introducing synchronised sound to animated pictures, a ground-breaking feat at the time.

The route to success was anything but smooth. Early financial difficulties threatened the young studio’s survival, and arguments over intellectual property rights almost cost them their most popular characters. The Great Depression added to the burden, yet it was at this time that the company created “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs,” the world’s first full-length animated film, in 1937. Critics questioned its potential, labelling it “Disney’s Folly,” but its massive success silenced doubters and cemented the studio’s position as an animation pioneer.

World War II offered a new set of obstacles, as many of the studio’s resources were transferred to aid the war effort. Despite these constraints, inventiveness thrived, producing classics such as “Dumbo” and “Bambi.” Later, labour strikes at the company questioned leadership and morale, but innovation remained at the forefront. The postwar years witnessed the expansion of live-action films, nature documentaries, and even television, opening the way for a more diverse portfolio.

By the 1950s, an idea for a theme park had taken root. The notion was more than just rides; it envisioned a totally immersive experience in which stories came to life. Despite financial and peer scepticism, the park debuted in Anaheim, California, in 1955. Disneyland was an instant success, allowing guests to experience realms of fantasy, adventure, and futuristic hopes. It was more than just a theme park; it was a showcase for limitless inventiveness.

The 1960s saw both triumphs and tragedies. As ideas for another park in Florida developed, health concerns surfaced. His untimely death in 1966 left much of the Florida project unfinished, but his crew continued his vision, resulting in the establishment of Walt Disney World in 1971. The park honours his long-held desire of providing a venue for families to make lasting memories together.

Today, the name reaches well beyond the guy himself. His company has expanded into a global behemoth that includes film studios, theme parks, streaming services, and other businesses. Iconic characters, captivating stories, and transforming experiences continue to inspire people throughout the world. More than a century after his birth, the ideas of creativity, inventiveness, and resilience remain central to his legacy.

This exceptional individual’s story is more than just a success story; it is a lesson in perseverance, invention, and the power of aspirations. His biography demonstrates that the most exceptional successes frequently begin in humble circumstances, and that vision, even in the face of adversity, may result in the creation of something everlasting. The universe he envisaged continues to inspire dreamers, innovators, and visionaries all across the world.